Lochinvar

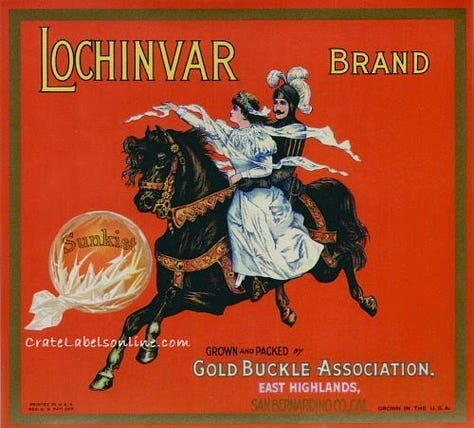

by Sir Walter Scott

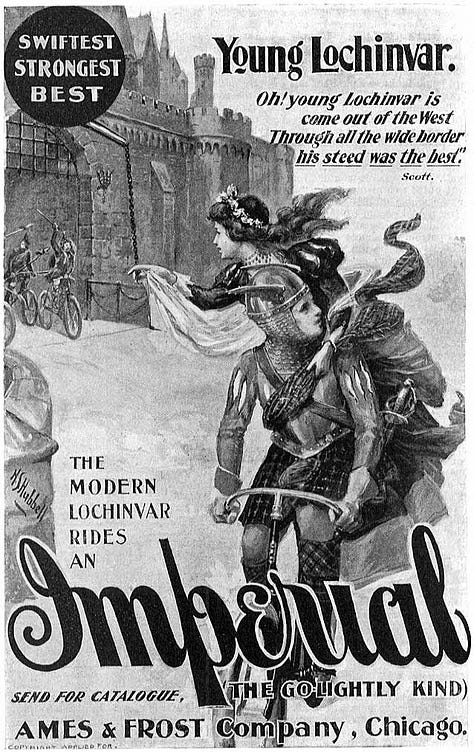

O young Lochinvar is come out of the west, Through all the wide Border his steed was the best; And save his good broadsword he weapons had none, He rode all unarm’d, and he rode all alone. So faithful in love, and so dauntless in war, There never was knight like the young Lochinvar. He staid not for brake, and he stopp’d not for stone, He swam the Eske river where ford there was none; But ere he alighted at Netherby gate, The bride had consented, the gallant came late: For a laggard in love, and a dastard in war, Was to wed the fair Ellen of brave Lochinvar. So boldly he enter’d the Netherby Hall, Among bride’s-men, and kinsmen, and brothers and all: Then spoke the bride’s father, his hand on his sword, (For the poor craven bridegroom said never a word,) “O come ye in peace here, or come ye in war, Or to dance at our bridal, young Lord Lochinvar?” “I long woo’d your daughter, my suit you denied;— Love swells like the Solway, but ebbs like its tide— And now I am come, with this lost love of mine, To lead but one measure, drink one cup of wine. There are maidens in Scotland more lovely by far, That would gladly be bride to the young Lochinvar.” The bride kiss’d the goblet: the knight took it up, He quaff’d off the wine, and he threw down the cup. She look’d down to blush, and she look’d up to sigh, With a smile on her lips and a tear in her eye. He took her soft hand, ere her mother could bar,— “Now tread we a measure!” said young Lochinvar. So stately his form, and so lovely her face, That never a hall such a galliard did grace; While her mother did fret, and her father did fume, And the bridegroom stood dangling his bonnet and plume; And the bride-maidens whisper’d, “’twere better by far To have match’d our fair cousin with young Lochinvar.” One touch to her hand, and one word in her ear, When they reach’d the hall-door, and the charger stood near; So light to the croupe the fair lady he swung, So light to the saddle before her he sprung! “She is won! we are gone, over bank, bush, and scaur; They’ll have fleet steeds that follow,” quoth young Lochinvar. There was mounting ’mong Graemes of the Netherby clan; Forsters, Fenwicks, and Musgraves, they rode and they ran: There was racing and chasing on Cannobie Lee, But the lost bride of Netherby ne’er did they see. So daring in love, and so dauntless in war, Have ye e’er heard of gallant like young Lochinvar?

As I noted two years ago in the New York Sun, whatever you need for memorable narrative verse, whatever you want for reading aloud, whatever you hope for thrilling romantic tales, you won’t find much better than the poem by Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832) that begins “young Lochinvar is come out of the west.” It gallops, it swoons, it mocks, and it triumphs. “So daring in love, and so dauntless in war, / Have ye e’er heard of gallant like young Lochinvar?”

Sir Walter Scott — whose birthday is today, August 15 — was the best-known British poet in the early years of the 19th century, writing such long narrative poems as The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805) and The Lady of the Lake (1810).

The British bought the books in droves, while on the continent the Europeans took Scott (1771–1832) as the model of romanticism (which is why so many Italian operas were made from his work). But then came Lord Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1812–1818), and Scott was clever enough to recognize that the ground of romantic poetry had shifted. He mostly gave up verse, turned instead to prose fiction — with his historical tales and Scottish stories racing through such novels as Ivanhoe, Rob Roy, The Bride of Lammermoor, and nearly two dozen more.

His poetry never slipped into obscurity, however, and the popular Victorian anthologies made set pieces for recitation out of extracts from his books — notably “Lochinvar,” from Canto 5 of Marmion (1808). In eight six-line stanzas of rhymed couplets of anapestic tetrameter (ba BAM / ba ba BAM / ba ba BAM / ba ba BAM), Scott tells of the young knight who swept into his love’s wedding feast, persuaded the bride to elope with him, and galloped away — while her weak would-be bridegroom, “a laggard in love, and a dastard in war,” stood by, in an image of impotence, “dangling his bonnet and plume.”

News

In our first six months, Poems Ancient and Modern has gained thousands of subscribers and followers. And in celebration of our first half year, we’re offering a limited-time special rate of half off, to encourage free subscribers to upgrade to paid subscriptions. Won’t you join us? Just $30 a year for poems five days a week.

I suppose the writer of The Graduate took his story from this poem ;)

I'm intrigued by the rhymes. Even in the broadest Scots, "war" and "far" are not the same sound. So do we say his name Lochinvore, to rhyme with war, or Lochinvah, to rhyme with far? "Scaur", a Scots word for a cliff or bank, is pronounced /skɔː/ (ɔ is the ô sound in [British pronounced] law, caught, thought) which perhaps suggests the former.