Ad Ministram

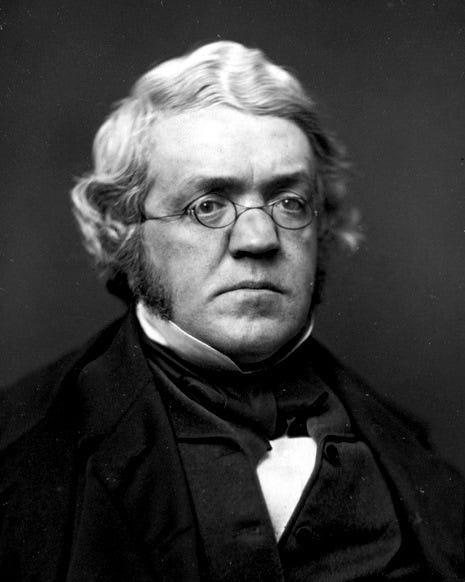

by William Makepeace Thackeray

Dear Lucy, you know what my wish is, — I hate all your Frenchified fuss: Your silly entrées and made dishes Were never intended for us. No footman in lace and in ruffles Need dangle behind my arm-chair; And never mind seeking for truffles, Although they be ever so rare. But a plain leg of mutton, my Lucy, I pr’ythee get ready at three: ◦ pr’ythee = prithee: pray thee, ask you Have it smoking, and tender, and juicy, And what better meat can here be? And when it has feasted the master, ’Twill amply suffice for the maid; Meanwhile I will smoke my canaster, ◦ canaster = coarse tobacco And tipple my ale in the shade. ═════════════════════════

Though known for his novels, William Makepeace Thackeray (1811–1863) wrote enough poetry to fill a thick volume in his collected works — perhaps unsurprisingly, given how much the man churned out: fiction, of course, but endless satirical commentary as well, including the essay in which Today’s Poem appears: his “Memorials of Gormandizing,” first published in Fraser’s Magazine, June 1841.

I’ve been fascinated by the tides of Thackeray’s reputation — if only because around a hundred years ago, fifty or sixty years after his death, he was often taken as Charles Dickens’s equal or even superior among Victorian novelists, and readers were expected to know his characters the way they still know (to some degree) Dickens’s. In the 1915 lecture, “The Moral Obligation to be Intelligent,” for example, John Erskine (a key figure for the emerging Great Books movement) mentions Thackeray’s Laura, Lady Castlewood, Beatrice Esmond, Becky Sharp, Harry Foker, Arthur Pendennis, and Colonel Newcome, supposing general audience recognition. Who now can field a reference to those characters? We’ve turned away from Thackeray perhaps harder than from any other once-canonical novelist.

In Today’s Poem, “Ad Ministram” (“To [my] ministra,” a female servant), Thackeray asks for a simple menu on a simple table, with two eight-line stanzas (each really two quatrains run together, rhymed abab–cdcd) in a comic trimeter of mostly three-beat feet: And TÌP-ple my ÀLE in the SHÀDE.

What he has in mind is a play on one of Horace’s most famous Odes: 1.38, “Persicos Odi,” in which the Roman poet tells his serving boy to discard extravagant Persian affectations and simplify back to country manners, drinking wine in a farm arbor. A reasonable 19th-century translation by William Trent renders it:

I hate your Persian trappings, boy,

Your linden-woven crowns annoy,

Cease searching for the spot where blows

The lingering rose.To simple myrtle nothing add;

The myrtle misbecomes, my lad,

Nor thee nor me drinking my wine

’Neath close-grown vine.

Thackeray, naturally for a 19th-century Englishman, translates decadent Persian trappings into “Frenchified fuss,” the serving boy into a serving girl named Lucy, and the wine into ale, as he asks for simple food. The context, amid his prose accounts of “gormandizing,” actually concerns the economics of the meals he tries in France:

Very few men can afford to pay more than five francs daily for dinner. Let us calmly, then, consider what enjoyment may be had for those five francs; how, by economy on one day, we may venture upon luxury the next; how, by a little forethought and care, we may be happy on all days. Who knew and studied this cheap philosophy of life better than old Horace before quoted? Sometimes (when in luck) he chirruped over cups that were fit for an archbishop’s supper [Ode 2.14.28]; sometimes he philosophized over his own ordinaire at his own farm.

Thackeray then prints the Latin text of Horace’s 1.38 as “To his Serving Boy” alongside the English text of his loose adaptation, “Ad Ministram” (jokingly giving the Latin original an English title, and the English translation a Latin one).

The 21st century has seen some new examinations of Horace’s reputation during various eras of English history. (See, for example, the essays in L.B.T. Houghton and Maria Wyk’s Perceptions of Horace [2010] and Stephen Harrison’s Victorian Horace [2017].) We should note, however, that this is an old interest. In 1918, the nearly forgotten classicist Elizabeth Nitchie (author of Vergil and the English Poets) counted around 200 Latin quotations in Thackeray’s work — and pointed out that a good majority, 140 of them, were from Horace, in service of claiming that Horace and Thackeray share a nearly identical sense of social irony.

Thackeray would lightly render other Horace. In the 1840 A Pictorial Rhapsody he mentions Ode 3.2, “Which may be interpreted (with a slight alteration of the name of Ceres for that of a much more agreeable goddess)” as:

Be happy, and thy counsel keep,

’Tis thus the bard adviseth thee;

Remember that the silent lip

In silence shall rewarded be.

And fly the wretch who dares to strip

Love of its sacred mystery.

My loyal legs I would not stretch

Beneath the same mahogany;

Nor trust myself in Chelsea Reach,

In punt or skiff, with such as he.

The villain who would kiss and peach,

I hold him for mine enemy!

It’s worth remembering the passage in his 1855 novel The Newcomes, where Thackeray has Colonel Newcome ask a Scotsman, “the best scholar in all India,” to judge the educational level of his son, Clive Newcome. And the Scotsman tells the father that the young man has acquired (at great public-school expense) only about “about five-and-twenty guineas’ worth of classical leeterature — enough, I daresay, to enable him to quote Horace respectably through life, and what more do you want from a young man of his expectations?”

Five-and-twenty guineas’ worth of classical leeterature. Not scholarship, certainly, but some recognition of the place of Horace in Victorian life.

We had an ongoing debate in my department about whether _Vanity Fair_ has any kind of real hero (or heroine) . . . I haven't read his poetry before now; this one is delightful and accords with my own views perfectly (except that I don't drink ale). Thanks for the interesting discussion of Thackeray's background and his relation to Horace.

Yeah, the point about Thackeray's reputation is interesting (I recall reading somewhere many years ago that at the start of the 20th century, The History of Henry Esmond was being talked about as one of the greatest English language novels ever). Catherine Peters discusses that a little bit in the early part of her biography of Thackeray; the irony that in his time the intensity of his cynicism was often criticized, but somehow then he was posthumously reimagined as some kind of avatar of Victorian middle class values.