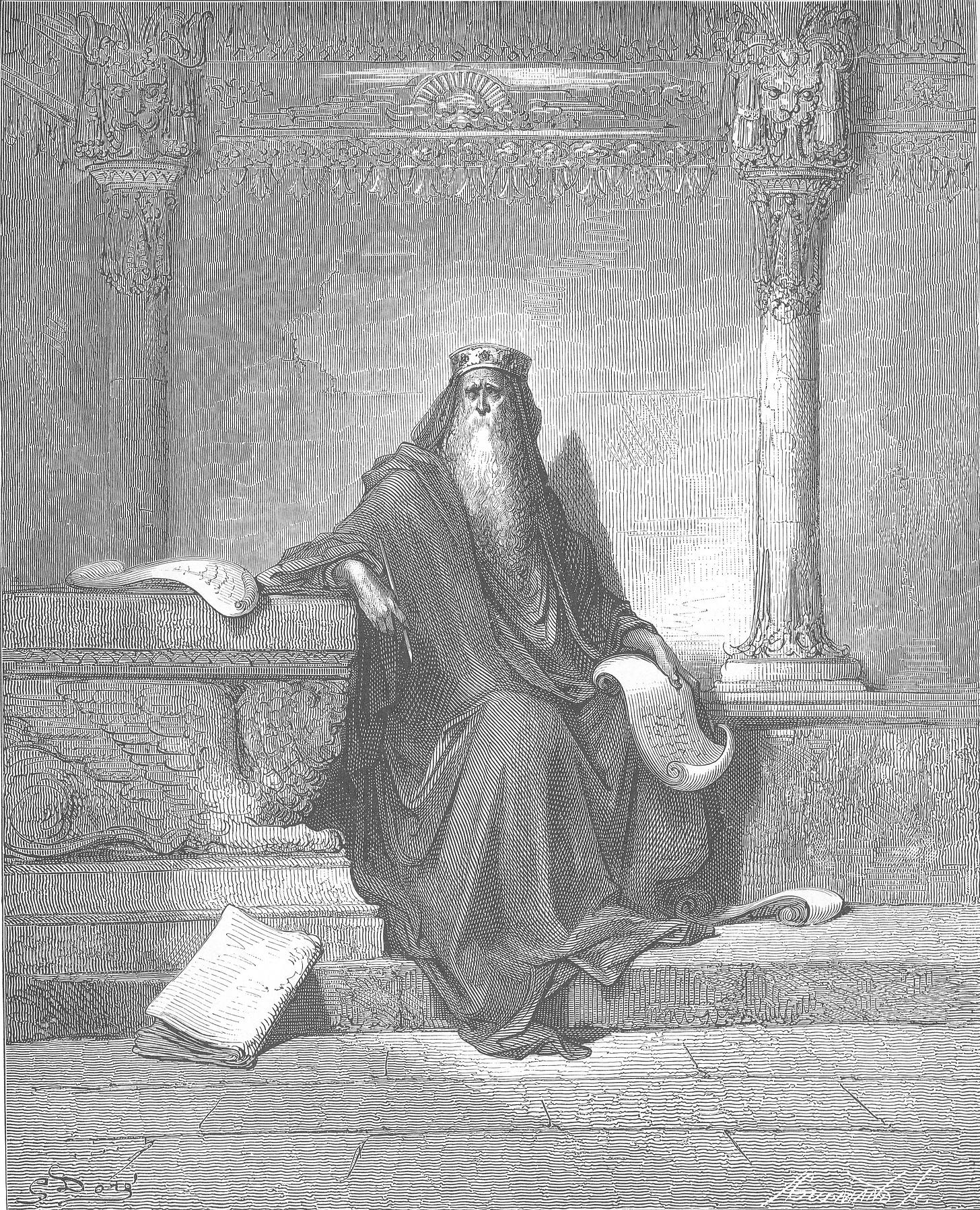

Today’s Poem: Vanitas Vanitatum

What profit hath a man of all his labour which he taketh under the sun?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poems Ancient and Modern to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.