To Celia

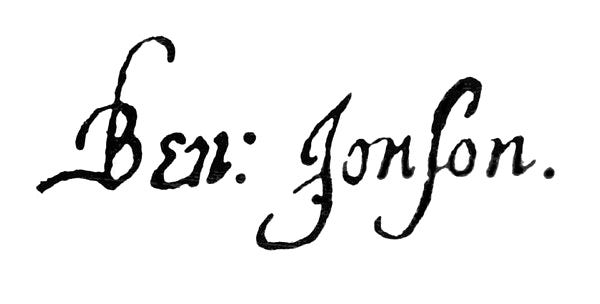

by Ben Jonson

Drink to me, only, with thine eyes, And I will pledge with mine; Or leave a kiss but in the cup, And I’ll not look for wine. The thirst, that from the soul doth rise, Doth ask a drink divine: But might I of Jove’s Nectar sup, I would not change for thine. I sent thee, late, a rosy wreath, Not so much honoring thee, As giving it a hope, that there It could not withered be. But thou thereon did’st only breathe, And sent’st it back to me: Since when it grows, and smells, I swear, Not of it self, but thee.

The Cavalier poets of the 17th century, courtiers clustered around King Charles I (1600–1649), descend from what we now call the English Silver Age poets. These earlier poets included the likes of Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503–1542) and Henry Howard, the Earl of Surrey (1517–1547): courtier poets when the court was that of Henry VIII (1491–1547).

Their literary generation, having imported the sonnet from Italy, began generally inventing a literature in modern English, all the while moving in and out of favor at Henry’s court. Wyatt (whose “Whoso List to Hunt” appeared as Today’s Poem on February 20) reputedly flirted with the queen, Anne Boleyn, which was tantamount to flirting with the headsman. Howard, cousin to both Anne Boleyn and her brief successor, Catherine Howard, did lose his head, largely for the crime of being related to queens accused of treason.

About the Silver Poets, the contemporary Irish poet Eavan Boland (1944–2020) once wrote that their “poems smell of the gallows.” Life, as they experienced it, was ambitious, treacherous, and often brief. It’s no real surprise that the Cavaliers, born into the next contentious century, should so readily have adopted the Silver Age trope of life and love as brevities to be grasped, even as everything flees away.

Between the Silver Poets and the Cavaliers, however, comes the man whom the Cavaliers explicitly claimed as their patriarch. They called themselves the “Tribe of Ben,” the literary heirs of Ben Jonson (1572–1637). Jonson, a contemporary of William Shakespeare (1564–1616), was born in the Tudor era, rose to fame as a dramatist in the Jacobean, and died in the doomed reign of the first King Charles.

His own inheritance from the Silver Poets was the emerging modern English poetry: all those sonnets, songs, and masques, as well as the dramatic forms that had begun to enliven the London stage. His legacy is apparent in the poems his Tribe produced. Sir John Suckling’s “Out Upon It,” for example, and “Song to Amarantha,” by Richard Lovelace, bear his congenital stamp. Readers here will also remember the Tribe’s “chaplain,” Robert Herrick, whose “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time” we featured here last week.

Jonson’s own elegant art of the love poem displays itself in today’s selection, “To Celia.” In common meter, alternating tetrameter with trimeter lines, and an intricate rhyme scheme of abcbabcbdefedefe, the poem first envisions love as a pledge drunk together, in a spirit more potent and ethereal than any wine. At the poem’s end, however, love is a spirit of another kind: the lover’s breath whose sweetness (strangely enduring, as an ordinary breath is not) imparts lingering life and her own fragrance to a wreath of flowers.

I guess it's passed out of pop culture now, so younger people may not know that for generations it was the text of a very popular song, with the first line as its title.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drink_to_Me_Only_with_Thine_Eyes

A striking number of performances listed there. I want to hear the one by Swans. Or maybe not.