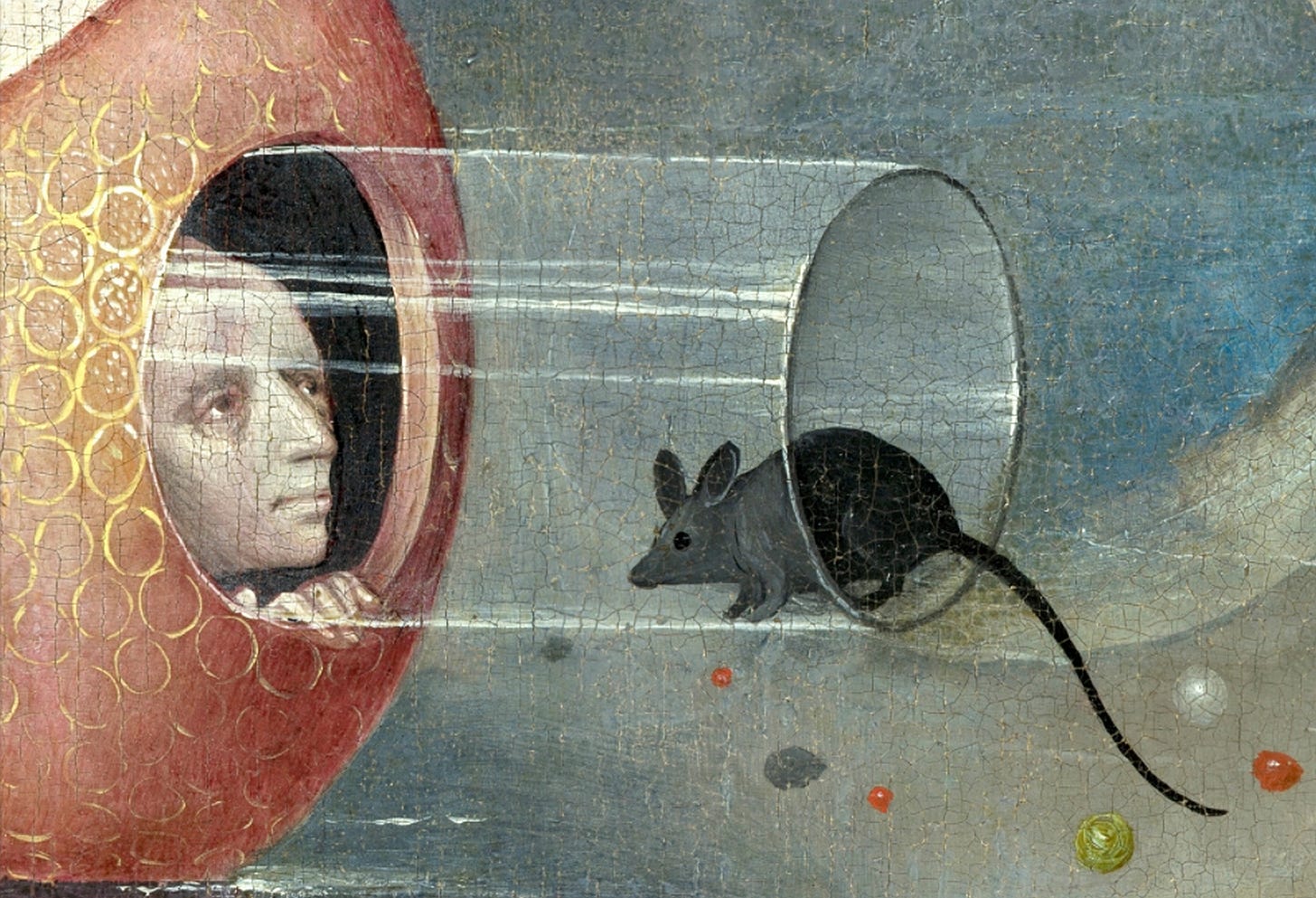

To a Mouse

by Robert Burns

On Turning her up in her Nest, with the Plough, November 1785.

Wee, sleeket, cowran, tim’rous beastie, ◦ little, sleek, cowering, timorous O, what a panic’s in thy breastie! Thou need na start awa sae hasty, Wi’ bickerin brattle! ◦ noisy rush I wad be laith to rin an’ chase thee Wi’ murd’ring pattle! ◦ pattle = paddle = plow’s blade I’m truly sorry Man’s dominion Has broken Nature’s social union, An’ justifies that ill opinion, Which makes thee startle, At me, thy poor, earth-born companion, An’ fellow-mortal! I doubt na, whyles, but thou may thieve; What then? poor beastie, thou maun live! A daimen-icker in a thrave ◦ a stray-grain in a large store ’S a sma’ request: of twenty-four sheaves I’ll get a blessin wi’ the lave, ◦ lave = remainder An’ never miss ’t! Thy wee-bit housie, too, in r…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poems Ancient and Modern to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.