The Shrouding of the Duchess of Malfi

by John Webster

Hark, now everything is still, The screech-owl and the whistler shrill, Call upon our dame aloud, And bid her quickly don her shroud! Much you had of land and rent; Your length in clay’s now competent: A long war disturbed your mind; Here your perfect peace is signed. Of what is’t fools make such vain keeping? Sin their conception, their birth weeping, Their life a general mist of error, Their death a hideous storm of terror. Strew your hair with powders sweet, Don clean linen, bathe your feet, And (the foul fiend more to check) A crucifix let bless your neck: ’Tis now full tide ’tween night and day; End your groan, and come away. ═══════════════════════

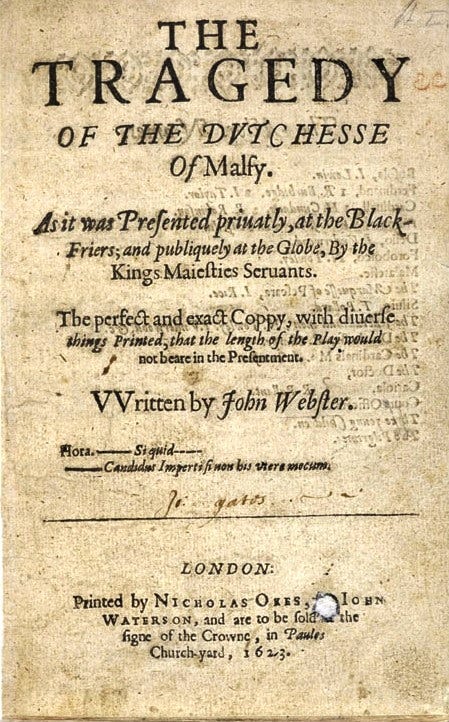

John Webster (c. 1578–c. 1632) was best known in his Jacobean time for his comedies and his many play-writing collaborations with the likes of Michael Drayton, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Middleton, William Rowley, John Ford, John Fletcher, Phillip Massinger, and Thomas Heywood — a near compendium of the playwrights of the era.

It was only in later centuries that his two major tragedies, The White Devil and The Duchess of Malfi, rose in critical appreciation. From the 18th century to the 20th century, he was considered a major writer in English. T.S. Eliot, for example, described him as one of the few authors who saw “the skull beneath the skin,” a line of literary criticism so good it kept Webster in college Drama 101 reading lists for decades.

The Duchess of Malfi, published in 1623, opens with the marriage of the widowed duchess to a commoner, before it turns into a horror tale of revenge and murder. The play’s most complex — and horrifying — character is the killer, servant, and spy, Daniel de Bosola. And in Act 4, Scene 2, Bosola speaks to the duchess: “Here your perfect peace is signed.” In chilling lines of tetrameter couplets, he prepares her for her murder at his hands: “’Tis now full tide ’tween night and day; / End your groan, and come away.”

I tend to set the mention of birds in this shrouding scene in The Duchess of Malfi beside the birds in Cornelia’s dirge in the final act of Webster’s 1612 revenge tragedy, The White Devil: “Call for the robin redbreast, and the wren,” he writes — for “with leaves and flowers” these birds will lightly cover the “friendless bodies of unburied men.” We looked at that dirge a year ago, and such passages remind us of why T.S. Eliot (1888–1965) kept Webster in mind. “Cover her face; mine eyes dazzle: she died young.”

Eliot gestures toward the conclusion of Cornelia’s dirge in the first part of The Waste Land, and he alludes to The White Devil again in the fifth part. But it’s in his 1918 poem “Whispers of Immortality” that he deployed his his most famous description of the Jacobean playwright, “much possessed by death.”