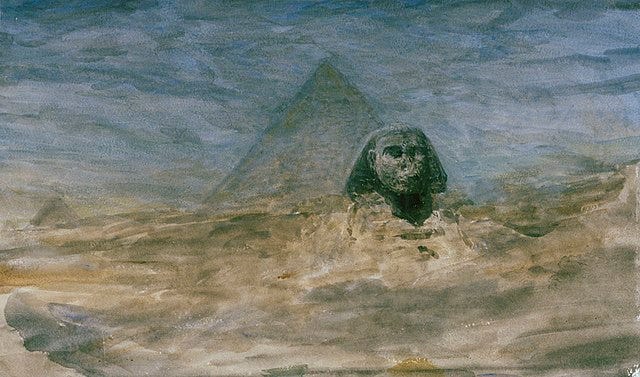

Today’s Poem: The Second Coming

The dawn of a new age is at hand, and we won’t much like it when it comes

We are living at a time near the end of the world. Our mirror has crack’d from side to side. Things fall apart.

A sense of doom has always been part of the human condition, of course. How could it not? Order always succumbs to chaos. Written into history is a tale of cataclysm. Written into the natural world is a story of entropy. Written into the self is awareness of death and decay. If we had no sense of transience and fragility, we would lack a piece of human experience — just as we would lack a piece if we had no sense of invention, progress, and improvement.

Still, some eras seem especially prone to a feeling of dissolution and dismay, with others given over to pride and progress. What is interesting about the 19th and 20th centuries is that they seemed to have both. Even as it climbed from height to height, the modern age was haunted by a sense that order — beauty, truth, the ceremonies of innocence — were bein…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poems Ancient and Modern to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.