The Rapture

by Thomas Traherne

Sweet infancy! O Heavenly Fire! O Sacred Light! How fair and Bright! How Great am I Whom the whole World doth magnify! O heavenly Joy! O Great and Sacred Blessedness Which I possess! So great a Joy Who did into my Arms convey? From God above Being sent, the Gift doth me enflame To praise his Name; The Stars do move, The Sun doth shine, to shew his Love. O how Divine Am I! To all this Sacred Wealth, This Life and Health, Who rais’d? Who mine Did make the same? What hand divine? ═══════════════════════

What we know of Thomas Traherne (1636/7–1674) is — as is so often the case — a matter of sketchy detail. His birth and baptism appear in no church records. He seems to have been the son of a Hereford shoemaker, or possibly an innkeeper, born into a family which, as the literary scholar Denise Inge (d. 2014) has suggested, in her introduction to Thomas Traherne: Poetry and Prose, might well have belonged to the seventeenth century’s emergent middle class.

His education, of which records do exist, took place at Hereford Cathedral School and Brasenose College, Oxford, and culminated in his receiving Holy Orders. From 1667 he served as private chaplain to Sir Orlando Bridgman, Baronet and Keeper of the Great Seal to Charles II. It was in Sir Orlando’s house that he died, in the autumn of 1674, leaving behind a body of work, bequeathed in a hasty will to his brother Philip, which would remain unread for the next two hundred years.

In the winter of 1897, one William T. Brooke of London rescued Traherne’s manuscripts from a bookstall’s trash barrow, mistaking them initially for lost works of Traherne’s contemporary Henry Vaughan (1621–1695), whose poem on “Christ’s Nativity” our readers will recall from last December. So Traherne’s own poems came at last to light.

Today Traherne remains a poet of relative obscurity. Yet Denise Inge described her first encounter with him, in an undergraduate anthology, as a life-changing experience. “I came convinced of my natural depravity, born a sinner in a world full of sin, and found in him glimpses of glory . . . What I found in Traherne was grace.”

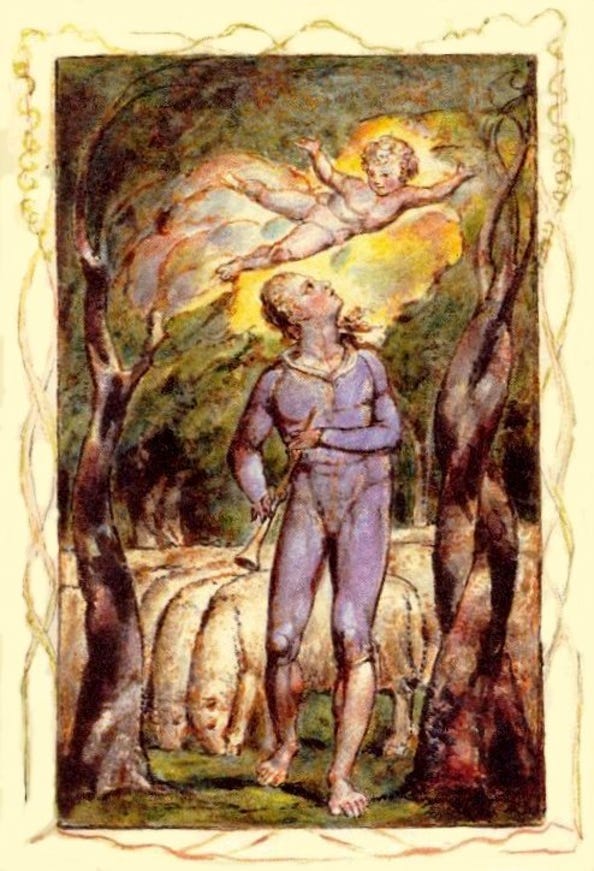

In Today’s Poem, we may discern what it is in Traherne that would cause a young and hungry soul to leap, like the unborn John the Baptist, with the joy of recognition. “The Rapture” seems almost a poem that William Blake (1757–1827), a hundred years later, might have written. Perhaps it’s only that final question — “What hand divine?” Did he who made the stars make me? — that summons the proactive ghost of Blake from further down the literary timeline.

But strangely, for a poem written in the generation after the great Metaphysical poets of the 17th century, by a devotional or spiritual poet generally classed as a Metaphysical, “The Rapture” doesn’t turn on a sense of man’s fallen insufficiency, as George Herbert’s poetry so often does. Instead, it envisions the human child in his “sweet infancy,” as a sacramental entity like the rest of creation, not only made by the “hand divine,” but indwelt by it and so imbued with a great measure of the same divinity.

We might be tempted to view Traherne as an influence for such poets as Wordsworth and Coleridge, in the early stages of their Romanticism — except that they almost certainly wouldn’t have read him. The only work Traherne published in his lifetime was a 1673 critique of the Catholic Church, entitled Roman Forgeries. From his own era to the dawn of 20th-century Modernism, Traherne’s poems lay dormant.

Though the poem vibrates with an expansive view of human potential that we might associate with a later period, its stanzaic structure suggests the influence of Herbert. There is the contrapuntal play of rhyme scheme and meter, two patterns that diverge and converge, like the separate melodic lines in polyphony. In each stanza, two of the a-rhymed lines, lines 1 and 4, are in dimeter, while line 5 is tetrameter. The b-rhymed lines, lines 2 and 3, are tetrameter and dimeter respectively.

This subtle melodic complexity, with the ebb and flow of longer and shorter lines, contributes to the sense of the speaker’s barely contained wonderment at his own condition. He rejoices in the recognition that the divine presence which indwells all creation also indwells himself. His very existence is not a smut in the eye of God, but an incident of grace.

On the second reading, I read it aloud. Then the musicality was beautifully apparent. Note to self: always read poetry out loud.

“Did he who made the stars make me?” Perfect!

Really interesting essay, Sally, thank you.