True wit, Alexander Pope once memorably suggested, shows us “What oft was thought, but ne’er so well express’d.” That’s a useful phrase to keep in mind when thinking about sayings, saws, truisms, mnemonics, adages, aphorisms, apophthegms — the whole range of moral and practical knowledge transmitted in brief and easily memorizable form, from “April showers bring May flowers” and “Thirty Days Hath September” to “Sohcahtoa” and “Righty tighty, lefty loosey.”

The poetic epigram, however, is something slightly different from the pithy saying that often called an epigram in prose, or even from an epigrammatical line or two in a longer poem.

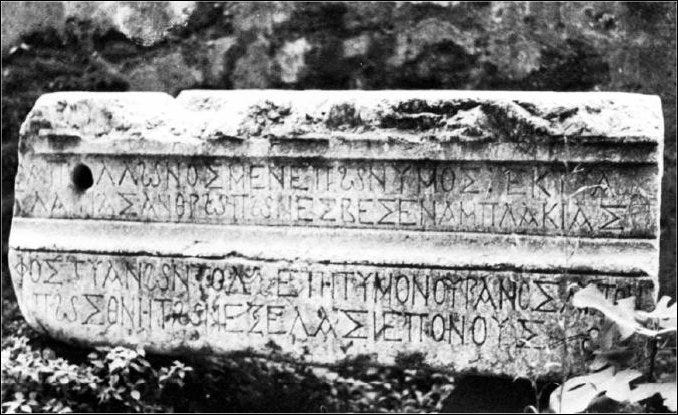

It’s a little hard to say quite what that difference is. Derived from the Greek for “inscription,” epigrams are literally poems short enough to be inscribed on stone, and the ancient Greek Anthology contains hundreds of them. But as the form passed to the Romans, it poured into ce…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poems Ancient and Modern to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.