Today’s Poem: The Convergence of the Twain

For Thomas Hardy’s birthday, tercets about the Titanic

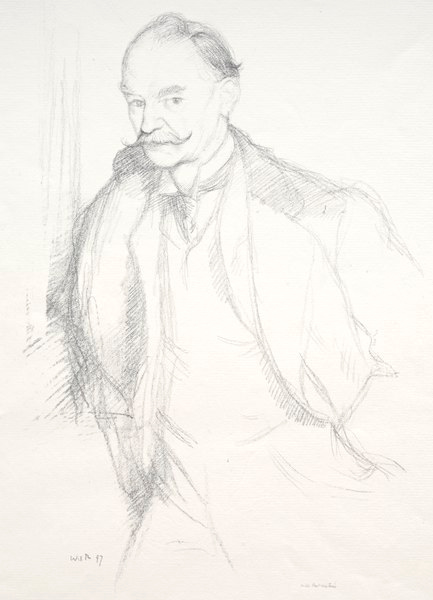

We’ve noted before in this space that even among the not-inconsiderable demographic of novelist-poets, or poet-novelists, of the last hundred years or so, Thomas Hardy (1840–1928) is unusual. Although he was writing poems by the age of sixteen, his serious emergence as a poet, with the publication of Wessex Poems in 1898, occurred as a tectonic shift from a two-and-a-half-decade career as a novelist. His last novel, Jude the Obscure, appeared in 1895, and from that time forward it was as if he had been reborn into a wholly separate literary form, a whole new and longer career ending only on his deathbed, with the composition of one last poem.

No artist owes the world an explanation for the failure of one form to satisfy any longer, or for the persuasive call of a different terrain that may prove larger and more imaginatively fertile. For Hardy, at any rate, poetry seems to have offered that larger terrain. This sounds paradoxi…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poems Ancient and Modern to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.