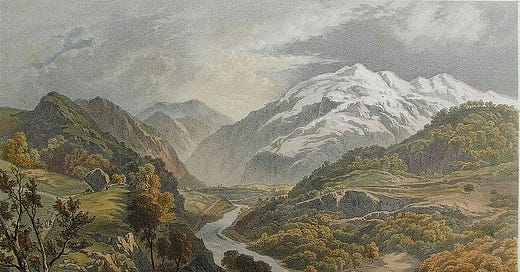

From the end of the 1790s to the end of his life, William Wordsworth (1770–1850) labored at his enormous, climactic, blank-verse opus, The Prelude. As early as 1798, in the Quantock Hills of Somerset, with his sister Dorothy to share his house (and his notebooks), and with Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834) for a neighbor and (sometimes) kindred spirit, Wordsworth had begun to set down the first fragmented passages, sketching recollections of the River Derwent and the beloved landscapes of his boyhood. These early, ruminative lines contain scenes that would appear for the last time in the 1850 edition of the poem, published three months after its author’s death and given its final, familiar title by his widow. But in their first fragmentary form, beautiful as these passages are, they are verses in search of something to be about.

By 1805, the year the first edition of the poem appeared in print, Wordsworth had written…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poems Ancient and Modern to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.