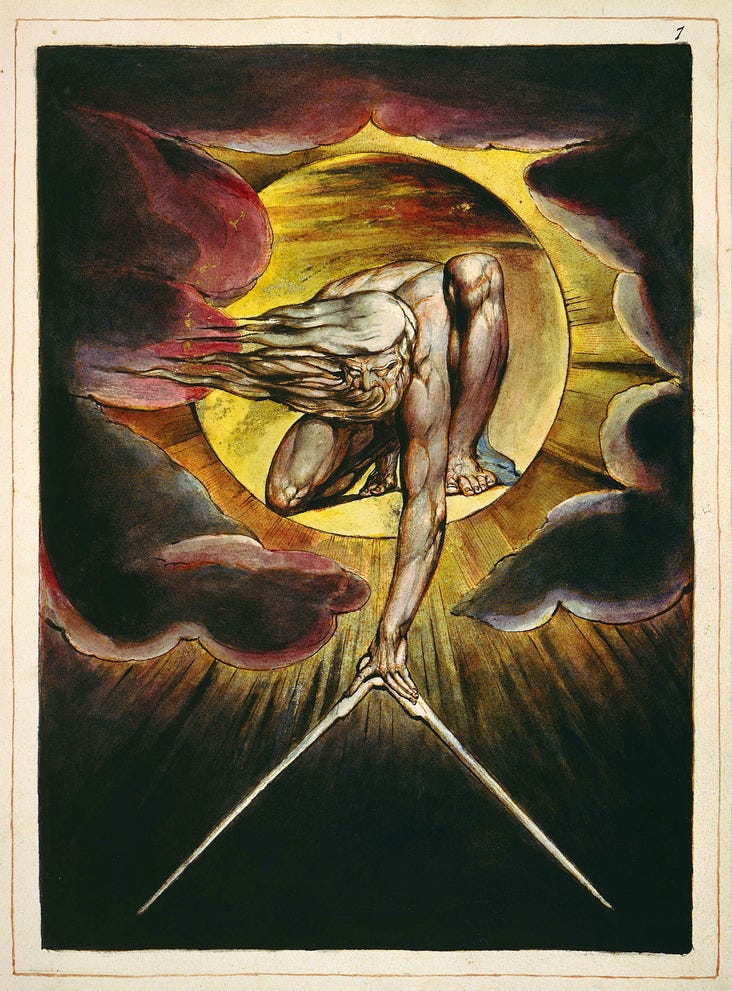

“The Atoms of Democritus / And Newton’s Particles of light / Are sands upon the Red sea shore / Where Israel’s tents do shine so bright,” William Blake (1757–1827) declared in “Mock on, Mock on, Voltaire, Rousseau,” a poem routinely taken as his rejection of science and Enlightenment reason.

It it, thoug…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poems Ancient and Modern to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.