He’s missing from the Norton Anthology of Poetry, his place in the chronology taken by . . . um, looks up the Table of Contents; ah, yes . . . Emma Lazarus (1849–1887) and her Statue of Liberty sonnet, “The New Colossus.” Harold Bloom’s The Best Poems of the English Language leaps from Byron to Housman. The 2006 Longman Anthology of Poetry steps over him. He just isn’t much placed in the tradition of English poetry any more.

Enough.

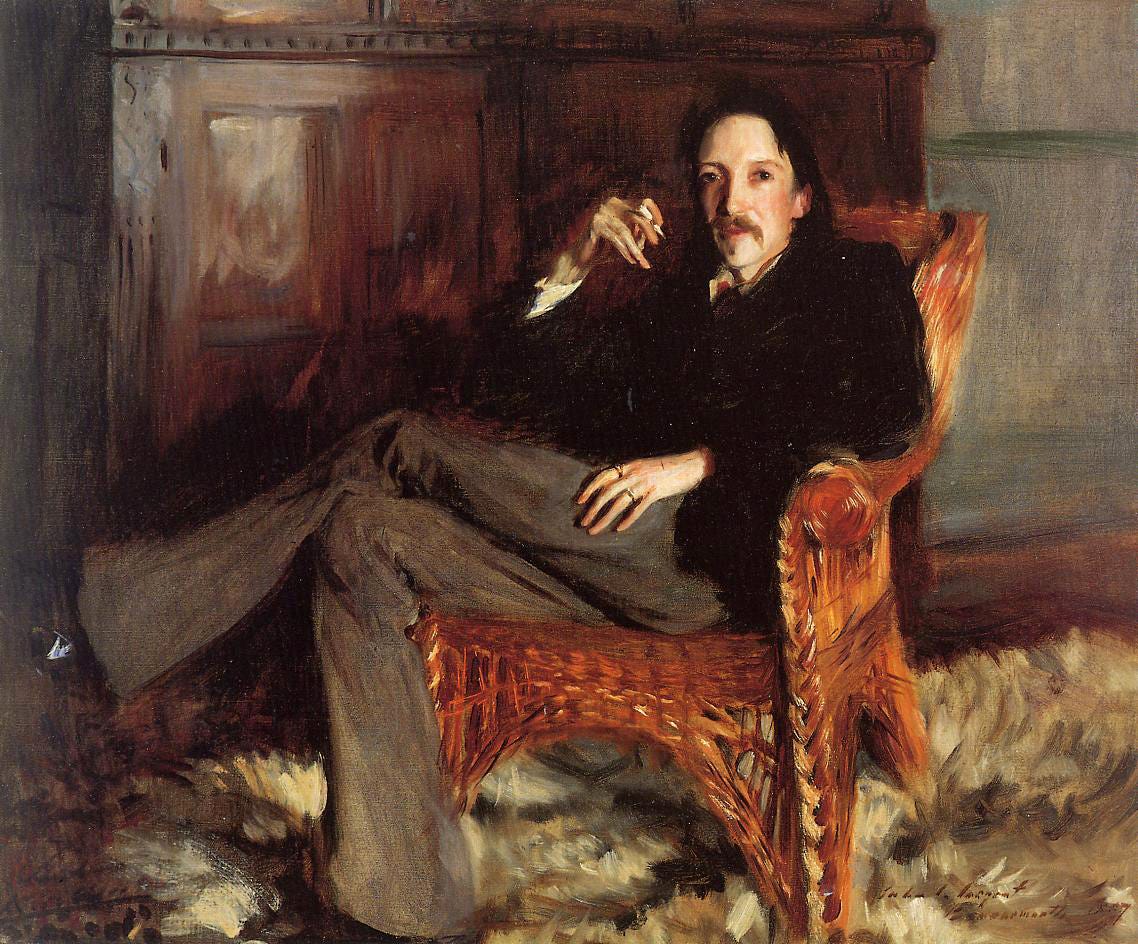

hereby devotes itself to the cause of Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894). Sure, he wasn’t the greatest poet. But there’s no sin in not being Milton or Wordsworth or Eliot, the world trembling at your touch. Some effort was made in the 1990s and early 2000s to restore his reputation, but that revival seems mostly to have sputtered out. We need to remember that Stevenson was fine, clever, and exact. A literature that can honor Emma Lazarus can surely find a spot at the table for Stevenson.Of course, he might be allowed only a grudging place at the children’s table. His 1885 A Child’s Garden of Verses was for many years the most widely read volume of children’s poetry after Mother Goose, topping the Late Victorians and the Edwardians who gave us a golden age of children’s books. And so, here at Poems Ancient and Modern, we will be featuring in coming weeks some of those children’s poems (especially on Wednesdays, when we try to present light or comic verse).

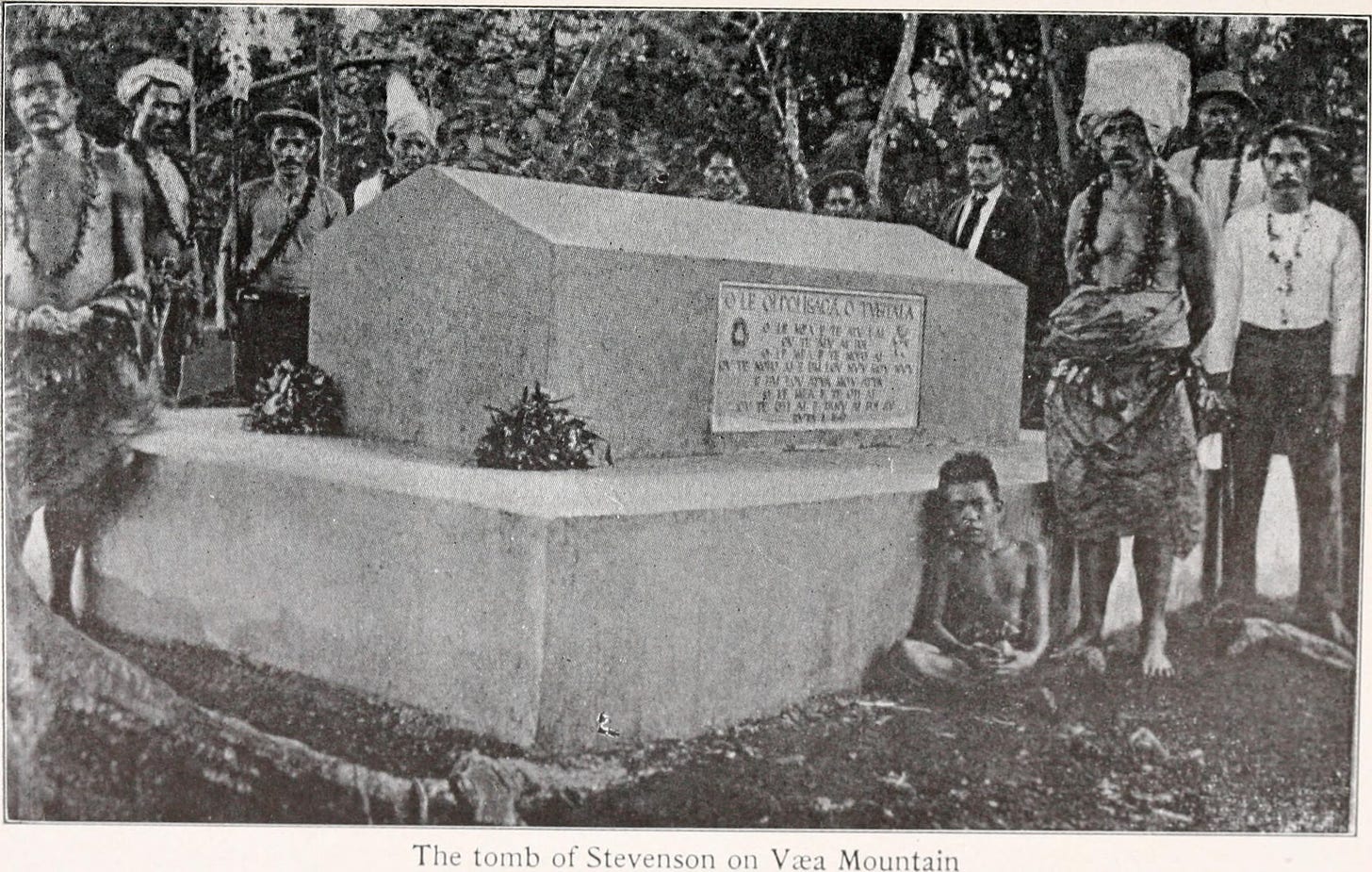

Today’s Poem, however, is one of Stevenson’s adult verses. We could look to his little-known work, praising his use of classical meters, his comedy, and his easy rhyming — but let’s start with what was, once upon a time, his most famous poem. Called “Requiem,” Today’s Poem is inscribed on his tombstone in Samoa (where he died of a stroke, after long suffering from consumption, at age forty-four).

With two quatrains of three four-beat lines followed by a three-beat line, the poem is rhymed aaab cccb, the last-line rhyme closing the poem like the lid of a well-made box. There’s a strong element of whistling-past-the-graveyard in the first stanza: Much as we’d like it to be true, nobody actually boasts at the moment of death, “Glad did I live and gladly die, / And I laid me down with a will.” It’s aspirational, but an aspiration worth holding.

And then comes the second stanza. Philip Larkin (1922–1985) took the title of what is his best-known poem these days — “This Be the Verse” (opening “They fuck you up, your mum and dad”) — from the first line of this Stevenson stanza. Larkin, our master of diction, surely intends irony in that choice for his anti-requiem, but his poem gains that irony from the aspiration of Stevenson’s. And Stevenson’s last lines have a rightness to them, a closure, an alliterative satisfaction that will not easily be dismissed: “Home is the sailor, home from sea, / And the hunter home from the hill.

Requiem

by Robert Louis Stevenson

Under the wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you grave for me:

Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

Remember A Child’s Garden of Verse from my childhood. If people had read it well, we would all be as happy as we kings.

Thanks for this! I'm sure the double meaning of "grave" (as in graven image, and the noun) is intentional.

So unjustly neglected, these writers damned with faint praise as "good but not among the great." I just finished reading all six of Trollope's Barsetshire novels, and found them a delight for their wit, their psychological complexity, and in a number of cases their refusal to reward you with the conventional "happy ending." My edition of The Last Chronicle of Barset features back-cover blurbs by Henry James and Nathaniel Hawthorne among others. But my impression is that now critics say "Oh, Trollope. Well, he's no Dickens or Austen." No, he isn't. Sometimes he's more entertaining.