Preludes

by T.S. Eliot

I The winter evening settles down With smell of steaks in passageways. Six o’clock. The burnt-out ends of smoky days. And now a gusty shower wraps The grimy scraps Of withered leaves about your feet And newspapers from vacant lots; The showers beat On broken blinds and chimney-pots, And at the corner of the street A lonely cab-horse steams and stamps. And then the lighting of the lamps. II The morning comes to consciousness Of faint stale smells of beer From the sawdust-trampled street With all its muddy feet that press To early coffee-stands. With the other masquerades That time resumes, One thinks of all the hands That are raising dingy shades In a thousand furnished rooms. III You tossed a blanket from the bed, You lay upon your back, and waited; You dozed, and watched the night revealing The thousand sordid images Of which your soul was constituted; They flickered against the ceiling. And when all the world came back And the light crept up between the shutters And you heard the sparrows in the gutters, You had such a vision of the street As the street hardly understands; Sitting along the bed’s edge, where You curled the papers from your hair, Or clasped the yellow soles of feet In the palms of both soiled hands. IV His soul stretched tight across the skies That fade behind a city block, Or trampled by insistent feet At four and five and six o’clock; And short square fingers stuffing pipes, And evening newspapers, and eyes Assured of certain certainties, The conscience of a blackened street Impatient to assume the world. I am moved by fancies that are curled Around these images, and cling: The notion of some infinitely gentle Infinitely suffering thing. Wipe your hand across your mouth, and laugh; The worlds revolve like ancient women Gathering fuel in vacant lots. ═══════════════════════

We’ve noted before, in discussing T.S. Eliot (1888–1965), that the anxious self-examination and self-curation which characterize the poems in the 1917 Prufrock and Other Observations mark the emergence of a poetic voice that even more than a hundred years later still sounds fresh to us. Or if not fresh, exactly, then familiar.

Encountering these poems, we recognize the soul-paralysis that too much self-probing can produce. We recognize the atomized self in its loneliness. We recognize the general griminess of the world — because we live in it. All the utopian visions, all the intended renewals of the human condition, have not exactly worked out the way they were supposed to. And here we are.

If the world of these “Preludes” appears to us in sharp familiarity, then, to our sorrow, we know why. Yet, especially on rereading, this familiar four-part invention yields to us more, perhaps, than we already know. The title, for example, recalls Wordsworth’s great “Prelude,” with its “spots of time” — a concept we’ve mused over in this space, more than once. Each of these “Preludes” presents the negative of a “spot of time,” a glimpse into a consciousness unrefreshed by any sweet memory, a banality of existence into which the sublime, if it exists, does not intrude.

Simultaneously, the title suggests the musical prelude, a fugue or suite of dances preceding some larger composition. Of course, part of the point here is that there is no larger composition, nothing that these scenes, lapping into each other, prepare for. Still, they belong to something beyond themselves: the poetic tradition, if nothing else, holds them as part of itself. They have not departed from it. Even in its apparent aimlessness, the poem is rhymed and metered. The predominant meter is tetrameter, though its regularity is disrupted by shorter lines in trimeter and dimeter and, in the final section’s last two stanzas, forays into pentameter: “I am moved by fancies that are curled,” “The notion of some infinitely gentle,” and that stunningly suggested response to the whole spectacle, “Wipe your hand across your mouth and laugh.”

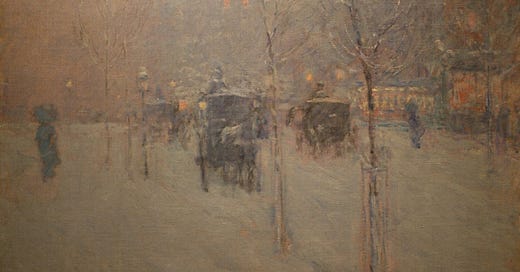

Beyond the sordidness of the material world, with its dirty city sights and smells, its dirty people, the speaker in the final “Prelude” does imagine something like a loving presence, that “infinitely suffering thing,” which at least is “gentle,” not cruel — though the absence of cruelty begins to seem a dubious virtue in a grayed-out reality. At any rate, the vision of that “suffering thing,” ambiguous as it is, remains only a “notion,” modern reality only a series of “vacant lots” in which prehistoric “ancient women” forage for scraps to kindle their paltry fire. Five years later, Eliot would open “The Waste Land” with that famous line, “April is the cruellest month.” But even that cruelty, the bitterness of spring, seems a beautiful, impossible fantasy to this endless urban winter.

The similarity of images in this poem and “Prufrock” suggests a linkage.

“burnt-out ends of smoky days” (“butt-ends of my days and ways”)

“sawdust-trampled street” (“sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells”)

“all the hands” (“all the works and days of hands”)

“fingers stuffing pipes” (“smoke that rises from the pipes”)

Possibly by giving up tobacco and insisting on sanitation we’ve lost access to a lot of the sensory world.

I think the final line of the first section "and then the lighting of the lamps" is a momentary spot of beauty in the grimness. At least it's always felt like that to me: a magic moment when suddenly the ugly urban landscape takes on a softer glow. It feels like it chimes with the "infinitely gentle, / Infinitely suffering thing."

And maybe it's just my romantic heart and my tenderness for Eliot, but I've always felt like the light creeping in between the shutters and the sparrows in the gutters are glimpses of something that could be lovely could be hopeful, that the poet in taking his inventory of the urban landscape notes. To me the poem has a rhythm that goes back and forth between the ugly and sordid and the little spots of something fairer that give the mind little islands of rest. Like Wordsworth's spots of time have diminished and grown dim, become mere freckles or ghosts flickering in the periphery of your vision, but aren't completely absent.