Pied Beauty

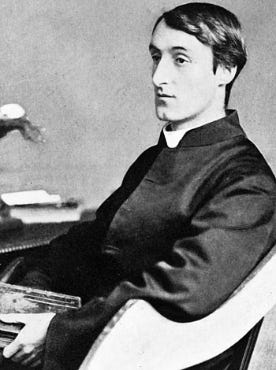

by Gerard Manley Hopkins

Glory be to God for dappled things —

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced — fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

═══════════════════════Come February, maybe, we’ll embark on a study of the “Terrible Sonnets,” the hard-won late-life achievement of Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889). But right now, in the Northern Hemisphere, anyway, sumer is icumen in, with all its bursting life, and it seems fitting to turn, yet again, to Hopkins’s own summertime of poetic flourishing. In the spring and summer of 1877, as Hopkins awaited the autumn and his priestly ordination, the sonnets we most readily associate with his name, voice, and vision flowed from him in a great surge: “The Windhover,” “God’s Grandeur,” “As Kingfishers Catch Fire” — and Today’s Poem, “Pied Beauty.”

This poem is one of three examples, in Hopkins, of the “curtal sonnet,” a form devised and named by the poet (the other two are “Peace” and “Ash Boughs”), and distinguished chiefly by its abbreviated length, ten and a half lines instead of the sonnet’s standard fourteen. More precisely, it is like a Petrarchan sonnet whose separate pieces have shrunk in the wash, or like a recipe with two ingredients, reduced proportionately. The Petrarchan octave becomes a sestet; the resolving sestet then consists of a quatrain and a fifth partial line. The rhyme scheme is compressed accordingly. The standard abba quatrain doesn’t repeat itself, but gives way instead to a cdecde sestet, with its first two lines forming the end of the initial stanza, broken after the d-rhyme, which is repeated an extra time in the short closing line.

The form’s compression raises the stakes subtly, requiring the poem to accomplish its Petrarchan wind-up/wind-down thought process in fewer lines, with less room at the end to tie that process off. If Hopkins’s primary fascination was with the mathematics involved in this reduction of the Petrarchan sonnet — he went so far as to work out the formula for paring it down with precision — the consequence, in “Pied Beauty,” is something that eludes quantification.

The world this poem holds in its brevity teems with life, even as some of its “sprung” pentameter lines teem with extra syllables and the possibility of more stresses. It’s only the the first and the penultimate lines, one in headless iambic pentameter, the other consisting of five perfectly straightforward iambs, that tells the reader for certain that this is the meter’s template, that line 3, for example, is meant to fit within that boundary.

Meanwhile, the particulars of creation show forth in their marvelous variety and variegation. They show forth, too, in the marvelous possibilities of the English language. In his notebooks, Hopkins worked at translations of Old English and Middle English poetry; his own poems, including this one, layer emphatic alliterative and assonantal repetitions of sound over the underlying pentameter, to reinforce that pattern even in its variations.

Look, for example, at line 3, whose twelve syllables make it, with the previous line, one of the two most maximalist pentameter lines in the poem. As much as the metrical context, this line’s assonance and alliteration shape how the reader hears the fall of accents. The double long o in “rose-moles” makes that hyphenated word a spondee. “All in stipple,” with its repeated l, sounds in the ear as a kind of musical triplet, moving quickly to its last word, “stipple,” which propels that ear forward through the reiteration of the p, t, and s, all contained in that single word, in the line’s conclusion: “upon trout that swim.” This is a meticulous structuring of the elemental sounds of English, vowel and consonant, so that the reader hears the requisite five stresses, even in a 12-syllable line.

For Hopkins, always, those particulars proclaim themselves, each thing unique and unrepeatable. But they also, even in their very strangeness, mirror the nature of their creator, which is — despite their variety — their common nature. The beautiful things of the world are trapped in its temporality: always in motion, always changing. Yet they have been “father[ed]-forth” by one “whose beauty is past change.” The only possible response is the poem’s abrupt, spondaic last line: “Praise him.”

A wonderful reading of this amazing poem.

What strikes me with this work is that Hopkins is not just describing the aesthetic positivity of pied colour-schemes (the beauty of trout, of the blue-white of summer skies and so on) but the *moral* complexity of the world:. "Fickle" is not a good thing to be (the Old English root of this world is stronger than the modern usage: ficol, from fician [“to deceive, trick”] = deceitful, crafty, false) though being freckled is morally neutral. But otherwise, in the quasi-sestet: better to be fast than slow, to be sweet than sour, to be bright than dim. But strong and weak, good and evil, are also part of the "dappled" cosmos God has created. Praise him indeed.

This is particularly satisfying to read in a quiet and beautiful spot -- overlooking a pond and the ocean on Nantucket Island where I have spent many hours watching a grandson fish and fuss with "gear and tackle and trim." Beautiful. Thank you!