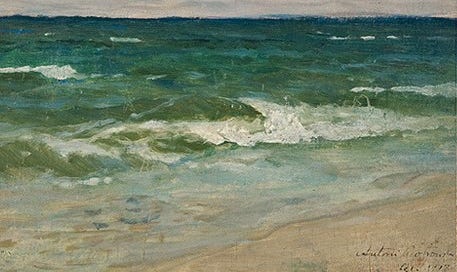

Today’s Poem: One Day I Wrote Her Name Upon the Strand

Edmund Spenser, the Spenserian sonnet, and the fond argument of lovers

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poems Ancient and Modern to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.