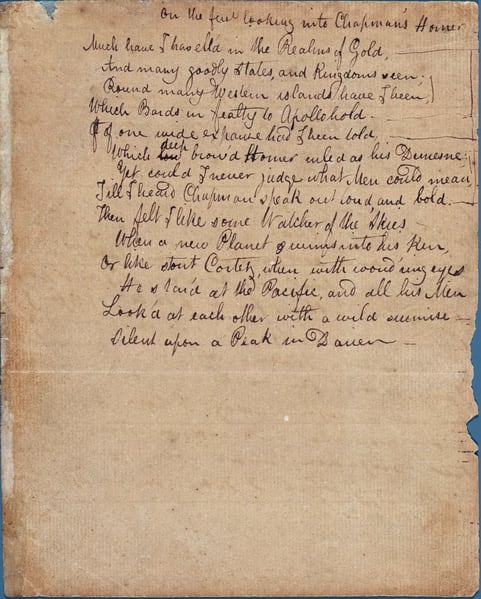

On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer

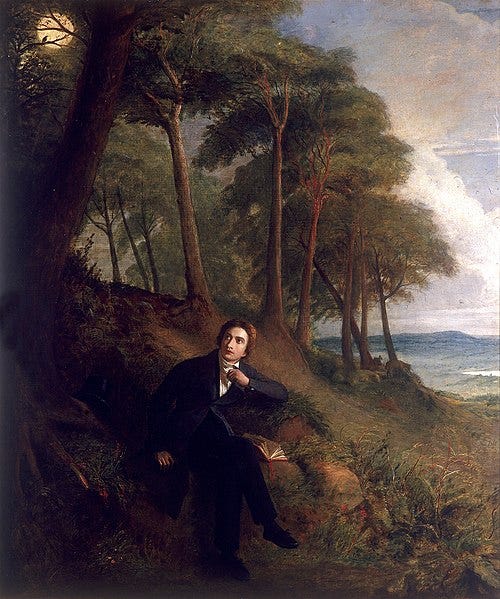

by John Keats

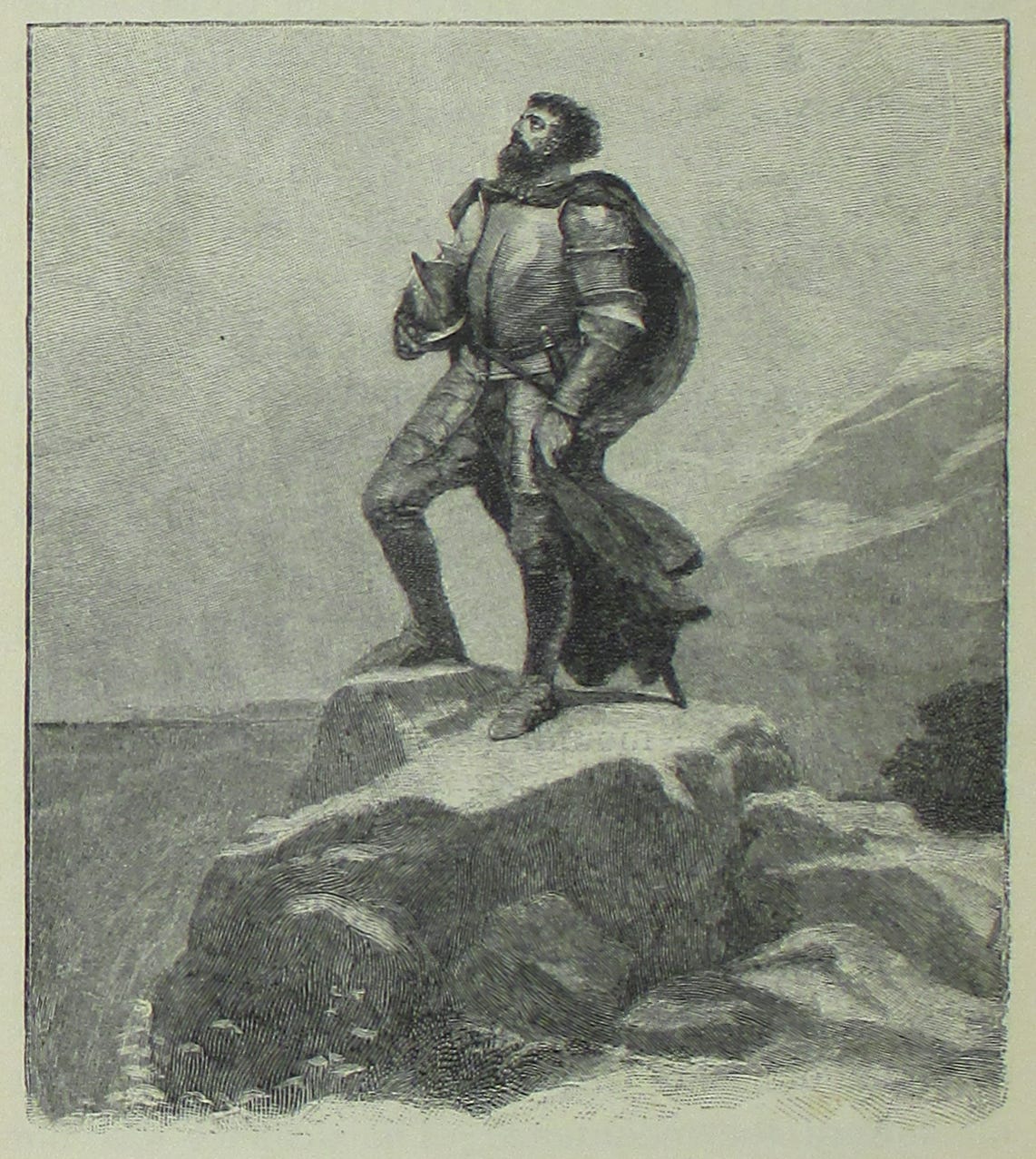

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold, And many goodly states and kingdoms seen; Round many western islands have I been Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold. Oft of one wide expanse had I been told That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne; Yet did I never breathe its pure serene Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold: Then felt I like some watcher of the skies When a new planet swims into his ken; Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes He star’d at the Pacific — and all his men Look’d at each other with a wild surmise — Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

In 1611, the English poet, playwright, and classicist George Chapman (1559–1634) published a complete translation of Homer’s Iliad. Thus, for the first time, did average English readers — at least those not classically educated — hear this voice of antiquity chanting its lines, so familiar to us now, across a chasm of millennia and more. In 1651, the Presbyterian minister-poet Samuel Sheppard (1624–1655) eulogized Chapman’s achievement in verse:

What none before durst ever venture on Unto our wonder is by Chapman done, Who by his skill hath made Great Homer’s song To vaile its bonnet to our English tongue, So that the learned well may question it Whether in Greek or English Homer writ?

And so on. But by far the most famous tribute to Chapman’s achievement — the sole reason many of us in the twenty-first century remember Chapman’s name at all — is the sonnet, written by John Keats (1795–1821) in the small hours of an October morning in 1816, which we offer as Today’s Poem.

What’s striking in this Petrarchan sonnet, especially in contrast to Sheppard’s poem, is that instead of a plodding ecomium in heroic couplets, Keats plunges headlong into the trope of reading as exploration, adventure, and discovery. To open Chapman’s Homer is to enter a new world of marvels. Even if it was Balboa, not “stout Cortes,” who first beheld the Pacific Ocean, we can’t help being struck, ourselves, at the end of the poem, by their “wild surmise,” as they fall silent on that “peak in Darien.” This, says Keats without belaboring his point — this is what it’s like. And even if we’ve never opened Chapman ourselves, we know what he means.

Such a great sonnet. I have a theory why Keats mistook "stout Cortez" for Balboa (schoolboy error) here: https://medium.com/adams-notebook/the-sea-had-soaked-his-heart-through-dd0053592166

I wonder if I knew the meaning 50 years ago when I studied it for A level. Or did we just declaim it and nobody understood it? Maybe everyone was just too embarrassed to ask.