My Heart Leaps Up

by William Wordsworth

My heart leaps up when I behold A rainbow in the sky: So was it when my life began; So is it now I am a man; So be it when I shall grow old, Or let me die! The Child is father of the Man; And I could wish my days to be Bound each to each by natural piety. ═══════════════════════

We might understand Today’s Poem, by William Wordsworth (1770–1850), as a kind of “pre-writing,” or seed-poem, for his larger and farther-reaching “Ode: Intimations of Immortality.” Wordsworth wrote “My Heart Leaps Up” in March of 1802, dashing it off the night before embarking on the “Intimations,” whose epigraph this poem’s last three lines became.

The first of those three lines — “The Child is father of the Man” — lodged itself in the English-speaking cultural consciousness, becoming the title of both a Beach Boys song (the Beach Boys’ “Surf’s Up” also quotes this line) and of the 1968 debut album from Blood, Sweat, and Tears. That is, the phrase lodged itself particularly in the English-speaking cultural consciousness of the 1960s when, as Joan Didion observed in her 1967 essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” various people for various reason were invested in the idea that “the kids” with their heightened insight were “trying to tell us something.”

In a 1954 essay on the “Immortality Ode,” the critic Thomas Raysor noted that Wordsworth, too — at least in his 1798 poem “We Are Seven” — felt that the kids were trying to tell him something. Specifically, he seems to have felt that the little girl with whom the poem’s speaker enters into dialogue is trying to tell this speaker, whose own adult vision of things has become clouded, that death is not erasure. The two children who “in the churchyard lie” exist in the present tense as much as she does. Though death separates them, just as going to sea or living at Conway has separated the others, some thread of immortality in that dead brother and sister connects them forever with the living.

In 1802, the 32-year-old Wordsworth was still trying to work out for himself a philosophy of the human soul and its relation to the larger reality inhabiting all the world outside the self, a reality whose infinite, immortal presence he intuited. Caught in time and borne forward by it toward the grave, could he truly hope that some part of himself, too, would be immortal, joined to that infinite presence? As Anthony Cirilla has argued, in later life Wordsworth “became . . . increasingly committed to the Church of England in direct proportion to how deeply [he] saw its orthodoxy as fulfilling the yearnings of the Romantic heart.” But in 1802, those “yearnings” remained a “natural piety” in search of explication — or at the very least, an “intimation” that his hope was not in vain.

On March 27 of that year, Wordsworth embarked on the longer poem in which he would attempt to work his questions and intuitions into some coherent explanation. But the night before, he wrote this briefer lyric, a kind of shorthand for the extended meditation that was surely already on the simmer in his mind.

If the last three lines of “My Heart Leaps Up” contain the core of the philosophical vocabulary for the coming poem, the shorter poem’s beginning, in lines 1 and 2, encapsulates that “natural piety,” the sense of connection between the speaker’s inner “heart” and the natural world, figured by the covenantal rainbow. We can understand the “heart” not merely as the seat of emotion, but as a figure for the entire inner life, encompassing reason, imagination, and moral conscience.

Significantly for Wordsworth, the heart’s action mirrors the arc of the rainbow, with its biblical resonances and its vibrant brief appearing, on a sky composed of storm and sun. Lines 3 through 5 posit that although time has passed and will continue to pass, something in that inner life will remain constant, and constantly responsive to that living presence in nature — or, as line 6 suggests, if that something in the inner life should become corrupted and cease to be, then “let me die.”

Formally, too, Today’s Poem seems a launching place for the “Intimations Ode.” Largely in tetrameter, with trimeter in lines 2 and 6, “My Heart Leaps Up” resolves itself in a line of iambic pentameter. Transferred to the position of an epigraph, that line touches off the spark of the longer poem’s form: octaves whose pattern begins in, departs from, and returns to pentameter.

“My Heart Leaps Up” stands on its own as a brief lyric, encapsulating the philosophy that Wordsworth sought, with dubious success (Raysor called it his “cloudy and baffling metaphysical idealism”), to clarify. But much of the poem’s fascination lies in the reflected glory of the longer, more ambitious work that immediately succeeds it — and in its place in the thought process that produced that work. Its immortality, in fact, and its status as more than merely a notebook outtake, derives from that connection with something larger: outside its own boundaries, yet always touching it.

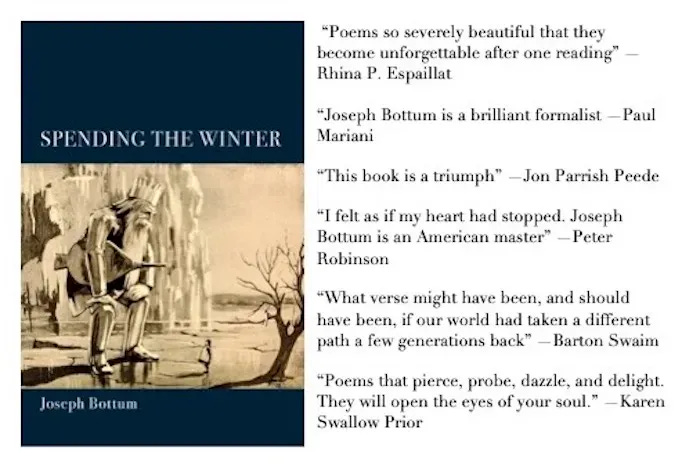

Thanks for that clear elucidation of the deceptively simple lyric and especially the connections with the wondrous Intimations Ode. Hard to understand that emotional “natural piety” finding fulfillment in Church of England orthodoxy, no? Odd how good W can be and also how prosaic, breathless, and, ripe for parody and bad imitation. (I can’t think of another good poet who has inspired so much bad poetry in others.) As you and Jody Bottum have demonstrated before, poetry is usually philosophical with “dubious success” and Raysor’s assessment (“cloudy and baffling metaphysical idealism”) has, of course, precedent in Byron’s witty judgements in Don Juan:

“So that their plan and prosody are eligible,

Unless, like Wordsworth, they prove unintelligible.”

“Thou shalt believe in Milton, Dryden Pope;

Thou shalt not set up Wordsworth, Coleridge, Southey;

Because the first is crazed beyond all hope,

The second drunk, the third so quaint and mouthy”

Those look like interesting articles you've linked, Sally. I appreciate the research!

Line 6 is actually a dimeter (fitting that the shortest and longest lines should be, respectively, in reference to death and the stretching out of days).