Mists in Autumn

by James Thomson

Now, by the cool, declining year condescend, Descend the copious exhalations, check’d, As up the middle sky unseen they stole, And roll the doubling fogs around the hill. No more the mountain, horrid, vast, sublime, Who pours a sweep of rivers from his sides, And high between contending kingdoms rears The rocky long division, fills the view With great variety; but in a night Of gath’ring vapour from the baffled sense Sinks dark and dreary; thence expanding far, The huge dusk gradual swallows up the plain: Vanish the woods; the dim-seen river seems Sullen and slow to roll the misty wave. Ev’n in the height of noon, oppress’d, the sun Sheds weak and blunt his wide-refracted ray, Whence glaring oft with many a broaden’d orb He frights the nations. Indistinct on earth, Seen through the turbid air, beyond the life Objects appear, and, wilder’d o’er the waste, The shepherd stalks gigantic: till at last, Wreath’d dun around in deeper circles, still Successive closing, sits the gen’ral fog Unbounded o’er the world, and, mingling thick, A formless gray confusion covers all.

For better or worse, we’re far likelier to know the chorus to “Rule Britannia” than we are to know its author’s name. Rather like the verses, to which nobody sings along, James Thomson (1700–1748) has faded, in the collective Anglophone memory, to a sort of human mumble between shouted rounds of that famous refrain.

Yet in his day, that brief halcyon day before the advent of Robert Burns (1759–1796) and his wee, sleeket, cowran, tim’rous beastie, Thomson was the Scots poet of the eighteenth century. His four-part poem, “The Seasons,” from which Today’s Poem is excerpted, was an enduring best-seller, with one edition gorgeously illustrated by Joshua Reynolds. The poem sold so well, in fact, that after Thomson’s death, its success gave rise to a dispute over the publishing rights and, in 1774, a ruling in the House of Lords which declared statutory limits to copyright — which is why we at Poems Ancient and Modern can commemorate, belatedly, Thomson’s September 11 birthday, by reprinting this section of his bestselling publication.

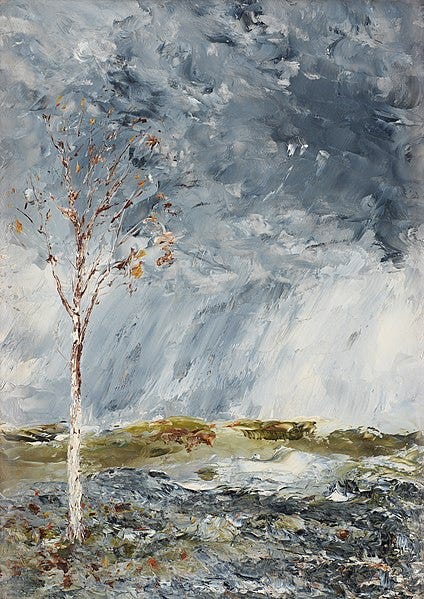

Like all of “The Seasons,” this relatively short excerpt demonstrates both Thomson’s facility with blank verse and his dramatist’s reading of a landscape. The poem unrolls like a stage set moving into place, its actors taking their positions. It’s intensely visual, but visual in the way that drama, that kinetic art, is visual. Its initial composition continually generates new compositions as its elements shift and change. Though no humans are present in this landscape, other than the speaker who narrates it, everything about it is infused with human feeling and consciousness. Though the speaker, like the author himself, remains offstage and anonymous, still he remains present in everything he sees.

Thomson sure deserves to be read more.

I read The Seasons years ago, in a volume that also included The Castle of Indolence, his poem in Spenserian stanzas.

Thanks first for the introduction to Strindberg as a painter. I know him as a writer indirectly, through Elias Canetti's description of his mother's passionate devotion to his works, but I didn't know that he was a painter.

I find the language in Thomson's nature scenes, like the one excerpted here, a bit tedious in its Miltonic inversions. Is "oppress'd" meant to modify "noon" or "sun"? If the Stanley Fish of "Surprised by Sin" were to take a look, he might say both, but that seems to give an easy out to the writer. I've noticed this problem in free verse (including mine, alas), so it's not simply a product of Thomson's aesthetic.

In a line from "Autumn" not included here, Thomson writes, "Strowed bibulous above I see the sands, / The pebbly gravel next...." He's writing about water as it works it way through soil strata down to "hardened chalk / Of stiff compacted clay." He can't just write, "I see strowed above the bibulous [absorbent] sands"--the meter's not right and the lack of inversion reveals an "unpoetic," straightforward statement, but at least a sensible one. I don't know exactly how a bibulous poet could be strowed about a landscape, but I'm willing to entertain the idea.

To the extent Thomson's descriptions are well observed, I can appreciate them.