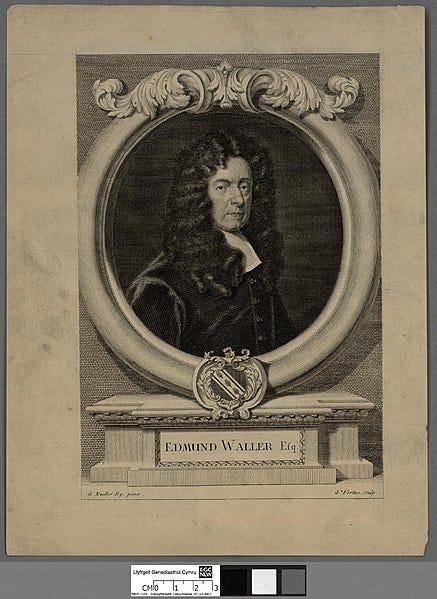

Born on this day in 1606, Edmund Waller (d.1687) was a major poet in his lifetime. And like his younger contemporary, Andrew Marvell (1621–1678), whose “To His Coy Mistress” appeared here last week, Waller was adept, through the upheavals of his century, at landing on his feet. Accused in 1643, in the midst of the first English Civil War, of participating in a plot to secure London for the beleaguered Charles I, he is said to have bribed his way out of a death sentence. Instead of execution, he faced banishment, which he endured in the form of a comfortable existence in Switzerland and France.

Conveniently related in some distant way to Oliver Cromwell, he returned to England in 1651. On the Restoration, he returned as well to the House of Commons, which he had first entered in 1624. Though remembered sourly in the century following his death as a mercenary politician and a fair-weather royalist, his elegantly measured formalism, particularly his embrace of the heroic couplet, made him an influence for such later poets as John Dryden and Alexander Pope

Though regarded now as a minor poet, significant chiefly as a progenitor of the Augustans, Waller excelled at the type of poem of which “Go, Lovely Rose” is a chief exemplar: the graceful lyric miniature, the perfect formal bibelot. On the one hand, “Go, Lovely Rose” says nothing that we haven’t already heard from more prominent poets of the same era. Yes, yes, life is short. Time’s a-wasting. You won’t be pretty forever, you know. Memento mori.

But on the other hand, look at what’s striking in this poem. Ordinarily, in the Cavalier mode, the speaker would address a girl, or possibly a group of girls, and direct them to look at the roses for instruction (see Robert Herrick’s “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time”) But in this poem, the speaker isn’t speaking to the lady in question. Instead, in three ababb quintains, airy as soap bubbles in their shifts from trimeter to tetrameter and back, this speaker addresses the rose.

He exhorts it to “go” and be what it always is in these poems: a figure for the brevity of youth and beauty. Go and tell her, he commands it, all the things a Cavalier lover would tell any woman, provided he were on speaking terms with her. Go and tell her, in fact, that this Cavalier lover tells her these things, by way of evocative proxy, because he’s finished with her. When it’s too late, which it already is, she’s the one who’ll be sorry.

(Song) Go, Lovely Rose

by Edmund Waller

Go, lovely rose! Tell her that wastes her time and me, That now she knows, When I resemble her to thee, How sweet and fair she seems to be. Tell her that’s young, And shuns to have her graces spied, That hadst thou sprung In deserts, where no men abide, Thou must have uncommended died. Small is the worth Of beauty from the light retired; Bid her come forth, Suffer herself to be desired, And not blush so to be admired. Then die! that she The common fate of all things rare May read in thee; How small a part of time they share That are so wondrous sweet and fair!