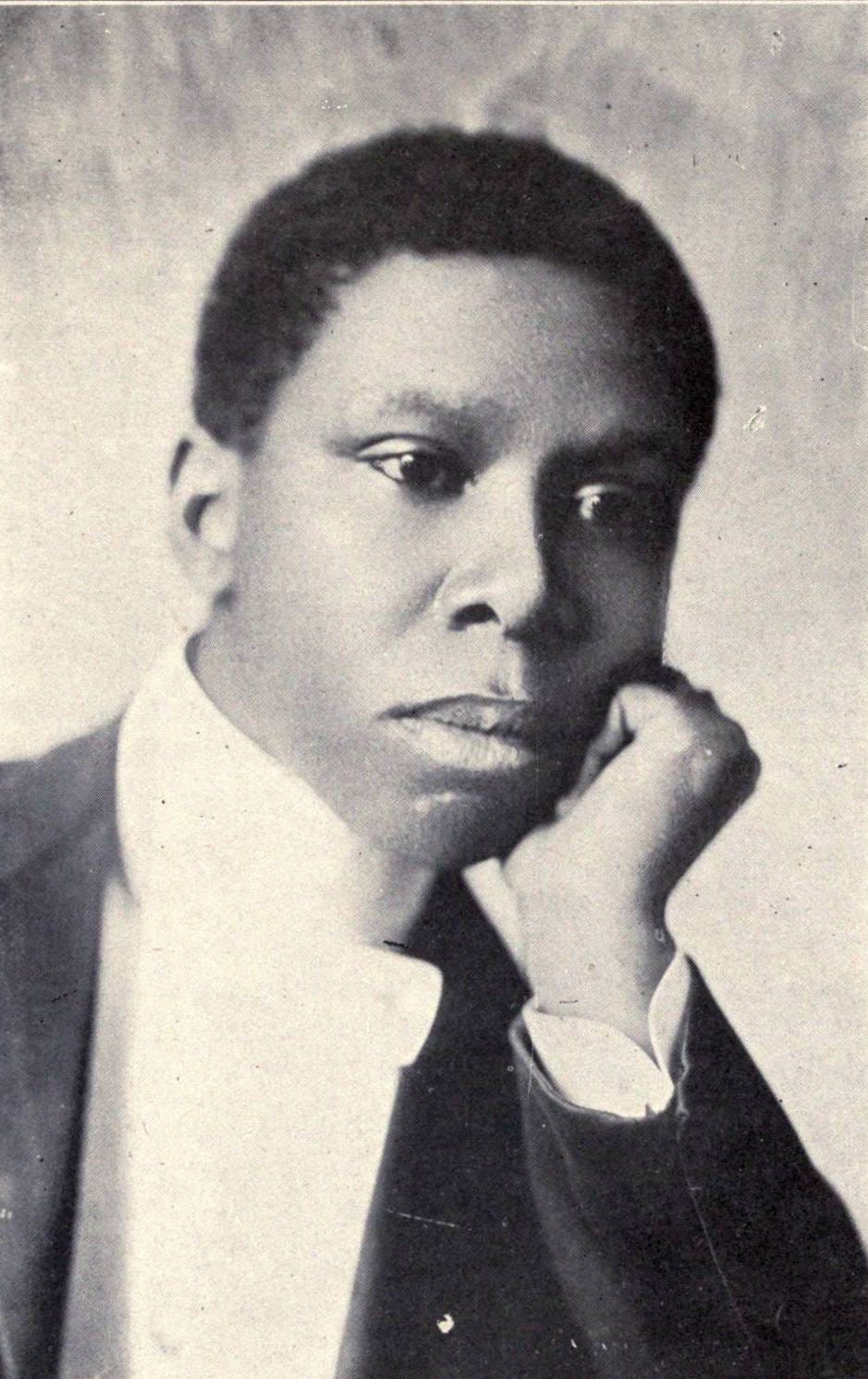

Emancipation

by Paul Laurence Dunbar

Fling out your banners, your honors be bringing, Raise to the ether your paeans of praise. Strike every chord and let music be ringing! Celebrate freely this day of all days. Few are the years since that notable blessing, Raised you from slaves to the powers of men. Each year has seen you my brothers progressing, Never to sink to that level again. Perched on your shoulders sits Liberty smiling, Perched where the eyes of the nations can see. Keep from her pinions all contact defiling; Show by your deeds what you’re destined to be. Press boldly forward nor waver, nor falter. Blood has been freely poured out in your cause, Lives sacrificed upon Liberty’s altar. Press to the front, it were craven to pause. Look to the heights that are worth your attaining Keep your feet firm in the path to the goal. Toward noble deeds every effort be straining. Worthy ambition is food for the soul! Up! Men and brothers, be noble, be earnest! Ripe is the time and success is assured; Know that your fate was the hardest and sternest When through those lash-ringing days you endured. Never again shall the manacles gall you Never again shall the whip stroke defame! Nobles and Freemen, your destinies call you Onward to honor, to glory and fame. ═══════════════════════

Once the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s began to be taken as the center of Black art — once Langston Hughes began to define African-American poetry — Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906) was bound to fade. The first post-bellum Black poet to find a national audience, he tended to write in two of the styles available to him at the end of the 19th century: in the dialect voices popularized by the Local Colorists, and the grand, hortatory voice of the tail end of the Fireside Poets.

Neither of these aged well in critical opinion after the modernist turn in the early 20th century, and if anthology editors occasionally included a Dunbar poem in their collections, it was mostly as a courtesy. Both voices — negro dialect verse, and the inspirational diction of social-uplift poetry — came to seem something of an embarrassment.

Make no mistake, Dunbar may deserve his tone in “Emancipation.” He was the son of two emancipated slaves, and this poem was, for him, a deeply intended call to a people to rise from where their stricken-off chains had left them on Emancipation Day. But hortatory, it is, with the first stanza the weakest:

Fling out your banners, your honors be bringing,

Raise to the ether your paeans of praise.

Strike every chord and let music be ringing!

Celebrate freely this day of all days.

and the last stanza the strongest as he warms to his topic:

Never again shall the manacles gall you.

Never again shall the whip stroke defame!

Nobles and Freemen, your destinies call you

Onward to honor, to glory and fame.

Besides, Dunbar was only eighteen when he wrote the poem in 1890. Built of seven stanzas of tetrameter lines, mostly dactylic and rhymed abab, the poem was written when Dunbar was just out of high school in Dayton, Ohio, where his mother had taken her children after being freed from slavery in Kentucky. (Because the world is always a smaller place than one thinks, it’s probably worth mentioning that Orville Wright was a friend and high-school classmate in Dayton.)

Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, and it reached the last of the Confederacy’s slaves in Texas on June 19, 1865 — which later became the Juneteenth holiday, gradually spreading from a local Galveston, Texas, celebration. In Dunbar’s Ohio, however, Emancipation Day was taken to be September 22, 1862 (when President Lincoln announced the coming proclamation), and it is this date that Dunbar had in mind when he called his audience to “Celebrate freely this day of all days.”

It’s in Dayton that Dunbar would die of tuberculosis far too early, at age thirty-three. William Dean Howells’s 1896 review in Harper’s of Dunbar’s second book, Majors and Minors, helped awaken interest in the man at the time, and his verse deserves a new look, now that the modernist distaste for the 19th century has abated at least a little. Last summer, for his June birthday, we looked at Dunbar’s more mature play with ballad meter in the poem “In Summer.” And this June we turn to the very young poet’s elevating call, where “Worthy ambition is food for the soul.”

His best-known poem, "We Wear The Mask", addresses the complications of what is now called "code switching" for Black Americans- the maintenance of a private identity that is substantially different from what was (is?) expected of them in public.

He was also a prolific writer of prose, authoring a large number of short stories and at least one novel. More so than his poetry, his prose is revelatory about how Black people existed in the time he was writing.

My love of the Fireside Poets has never wavered, so while I also enjoy poets of the Harlem Renaissance, I also read Dunbar with great pleasure.