Today’s Poem: Corinna’s Going A-Maying

Our life is short, and our days run / As fast away as does the sun

Corinna’s Going A-Maying

by Robert Herrick

Get up, get up for shame! The blooming morn

Upon her wings presents the god unshorn.

See how Aurora throws her fair

Fresh-quilted colours through the air:

Get up, sweet slug-a-bed, and see

The dew bespangling herb and tree!

Each flower has wept and bow’d toward the east

Above an hour since, yet you not drest;

Nay! not so much as out of bed?

When all the birds have matins said

And sung their thankful hymns, ’tis sin,

Nay, profanation, to keep in,

Whereas a thousand virgins on this day

Spring sooner than the lark, to fetch in May.

Rise and put on your foliage, and be seen

To come forth, like the spring-time, fresh and green,

And sweet as Flora. Take no care

For jewels for your gown or hair:

Fear not; the leaves will strew

Gems in abundance upon you:

Besides, the childhood of the day has kept,

Against you come, some orient pearls unwept.

Come, and receive them while the light

Hangs on the dew-locks of the night:

And Titan on the eastern hill

Retires himself, or else stands still

Till you come forth! Wash, dress, be brief in praying:

Few beads are best when once we go a-Maying.

Come, my Corinna, come; and coming, mark

How each field turns a street, each street a park,

Made green and trimm’d with trees! see how

Devotion gives each house a bough

Or branch! each porch, each door, ere this,

An ark, a tabernacle is,

Made up of white-thorn neatly interwove,

As if here were those cooler shades of love.

Can such delights be in the street

And open fields, and we not see’t?

Come, we’ll abroad: and let’s obey

The proclamation made for May,

And sin no more, as we have done, by staying;

But, my Corinna, come, let’s go a-Maying.

There’s not a budding boy or girl this day

But is got up and gone to bring in May.

A deal of youth ere this is come

Back, and with white-thorn laden home.

Some have despatch’d their cakes and cream,

Before that we have left to dream:

And some have wept and woo’d, and plighted troth,

And chose their priest, ere we can cast off sloth:

Many a green-gown has been given,

Many a kiss, both odd and even:

Many a glance, too, has been sent

From out the eye, love’s firmament:

Many a jest told of the keys betraying

This night, and locks pick’d: yet we’re not a-Maying!

Come, let us go, while we are in our prime,

And take the harmless folly of the time!

We shall grow old apace, and die

Before we know our liberty.

Our life is short, and our days run

As fast away as does the sun.

And, as a vapour or a drop of rain,

Once lost, can ne’er be found again,

So when or you or I are made

A fable, song, or fleeting shade,

All love, all liking, all delight

Lies drown’d with us in endless night.

Then, while time serves, and we are but decaying,

Come, my Corinna, come, let’s go a-Maying.

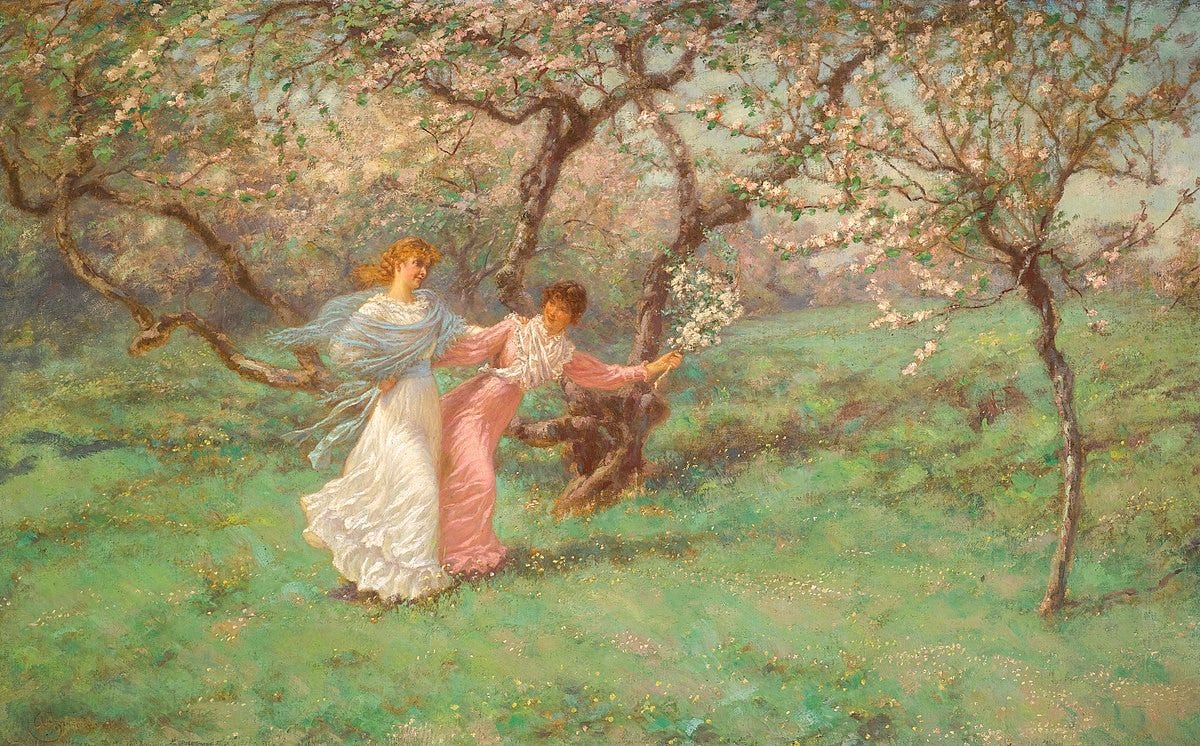

═══════════════════════The first thing to remark in Today’s Poem, by the 17th-century Anglican cleric and poet Robert Herrick (1591–1674), is the certainty of its title. As we quickly learn, in these five sonnet-length couplet stanzas, with their pentameter-tetrameter patterning, Corinna is not, in fact, “going a-Maying” — not yet, anyway. The poem itself, published in Herrick’s one enormous collection, the 1648 Hesperides, offers an exhortation, an argument, and an invitation to a girl who seems determined to sleep the day away instead of seizing it.

This poem’s speaker is in his way as much a lover of sophisms as the speaker of John Donne’s “Air and Angels.” But in Herrick’s poetic handling, the Cavalier poets’ carpe diem argument — time flies, sweetheart — becomes less a seduction ploy than a classically Stoic acknowledgment of human frailty. Readers here have seen already, in “To the Virgins, To Make Much of Time,” how Herrick undercuts the standard line about seizing the day with an injunction to seize it virtuously, at the nuptial altar. Even in fun, he catches a whiff of mortality and with it, the need not only to “make much of time,” but to make something meaningful of time.

So it is in the equally anthologized “Corinna’s Going A-Maying.” After clearing the hurdle of the title with its foregone conclusion, the second thing a reader might note is that Corinna herself — she who, as we have been told, is for sure “going a-Maying” — represents a comic and rather endearing turn on the pastoral archetype, whose namesake is the Corinna of Ovid’s Amores. Thanks to such translators as Christopher Marlowe (whose rendering of Elegy 5, from Book I of the Amores, we considered in February of last year), Corinnas turn up with some frequency in the pastoral poems and songs of the 16th and 17th centuries. If you need a fresh-cheeked maiden for your poem about sex and/or the countryside — so thought poets of the Tudor era and beyond — then Corinna’s your girl.

But as Herrick’s opening here makes clear, this Corinna is still in bed. In fact, by the end of the poem, she’s still still in bed, and (presumably) all by herself, too. In the last line, the speaker is still exhorting her, with redoubled urgency, to get up. The other flesh-and-blood nymphs of springtime are out rambling through the flow’ry meads “to fetch in May” — but not Corinna.

“For shame,” the speaker chides her in the first line, for as it turns out, her sleeping through May Day is not only a failure of fun but a moral failing as well. To frolic through those meads is not mere sport. It is a form of natural piety, practiced by the flowers who, having “wept,” now “bow toward the east,” and by the birds, whose mating songs are figured as “matins,” or morning prayer.

Successive stanzas develop this theme of natural devotion, as opposed, perhaps, to imposed forms of devotion. Just as Herrick’s “To Keep a True Lent” rejects formal Lenten penances in favor of a personal and inward conversion, so in the second stanza this speaker advises Corinna to be “brief in praying: / Few beads are best when once we go a-Maying.”

Just as nature has sanctified her own scenes, so the doors of the village are decked with branches, making each house “an ark, a tabernacle,” a holy space. In the following stanza, this integrated natural and human world, unified and sacralized by the springtime, becomes the place where the round of life perpetuates itself in marriage and sex, possibly but not necessarily in that order. All this is what the time is for — while “we are yet decaying.” Better to “go a-Maying” while you can, and embrace what life you can, than to decay, supine, among the sheets as in the grave, where you will find yourself, anyway, soon enough.

Again, these are sonnet-length stanzas, each composed of seven couplets: the first, fourth, and final in iambic pentameter, the rest in iambic tetrameter. At least, this is the template, with some rhetorical variation to underscore the speaker’s various angles of playful-serious attack. The shifts between pentameter and tetrameter in the overall pattern seem designed to shake Corinna awake.

But metrical substitutions, such as the trochaic foot — “Rìse and” — that opens the second stanza, communicate urgency by that initial, emphatic stressed syllable. Ditto the spondaic “Fear not” of the fifth line of the same stanza, where both those words have to bear the accentual weight in order for the line to read as tetrameter. There’s an odd moment, too, like a shifting of gears, in the fourth couplet of the final stanza, the expected pentameter first line completed by a rhyming mate in tetrameter.

Meanwhile, the closing pentameter couplet in each stanza reiterates the call to “go a-Maying.” Even as they repeatedly cajole, these refrains still echo the title, which proclaims with confidence, as an article of faith, that Corinna — though still, for the moment, asleep and unseen — is abandoning her solitary bed and “going a-Maying.”

Lovely analysis and what music in the last stanza. Along with Herrick one thinks of Marvell’s theatrical narrator in “To his Coy Mistress,” imploring, threatening, wryly remarking, “The grave’s a fine and private place / But none, I think, do there embrace”; (sad to report that today’s students largely dislike him and the poem). There is also Peter de Vries’ witty tribute to Marvell, “To his Importunate Mistress”; Robin Williams’ popularizing turn in Dead Poets Society, when he urges the class to look at the pictures of the former students who are “now pushing up daffodils” and hear them whisper, “Carpe diem,” which he rephrases as “Make of your lives something extraordinary.” All a long way from the grimly Stoic locus classicus, Horace 1.11 (Ut Melius quicquid erit pati, “how much better to endure whatever will be,” with its dark images of unknowable future winters and crashing sea waves preceding the advice to be wise, strain the wine, and cut back long hope. And then the final dark reflection: Dum loquimur, fugerit invida/ aetas; carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero, “While we speak, envious time will have fled; seize (pluck) the day, trusting in the next one as little as possible.” Such a rich topic. Thanks.

Thanks for introducing me to this poem. I think this is the closest the English language is gonna get to a xmas song playing loudly on the radio. Extraordinary energy and clear structure. I kept seeing bright colors while reading, but when I looked back at the poem the colors were not there. I think this is my first experience of synesthesia.