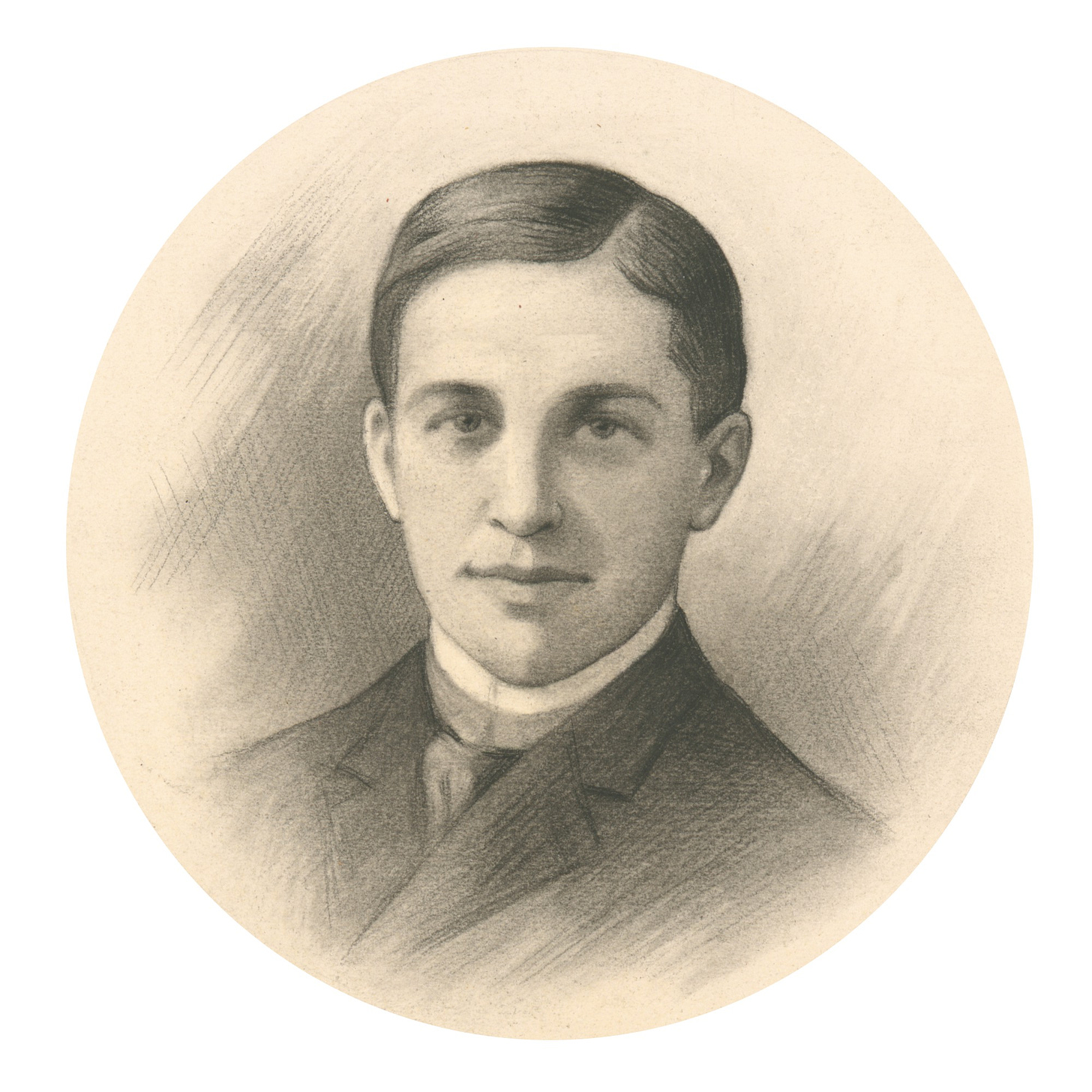

To learn how “Casey at the Bat” became America’s best-known baseball poem — maybe America’s best-known poem of any kind, rivaled only by “A Visit from St. Nicholas” — you have to begin with the fact that a young man named Ernest L. Thayer (1863–1940) went to Harvard.

It’s there in Cambridge that he edited the Harvard Lampoon alongside such brilliant undergraduates as George Santayana (1863–1952). And when his classmate (and business manager of the Lampoon), William Randolph Hearst (1863–1951), took over the San Francisco Examiner in 1887 with his family’s gold-mining money, Thayer followed his friend to California, helping out the fledgling newspaper publisher.

The Examiner is where, on June 3, 1888, Thayer (writing under the penname “Phin,” a college nickname) published a comic poem about an arrogant ballplayer on the Mudville nine. Despite the claims of various players at the time to be the original for Casey — and various towns, down to the present, to be the original for Mudville — Thayer always insisted the story and its details were entirely fictional.

The age of bitter newspaper rivalry was coming into full swing. (It would escalate dramatically when Hearst bought the New York Journal in 1895, and began to compete directly with other New York publications.) But, according to the most common account, a man named Archibald Gunter, visiting California, clipped the poem from the Examiner and, on his return to New York, gave it to a friend, the comedian De Wolf Hopper.

Liking the verses, thinking they would get a laugh when recited dramatically, Hopper added it to an August 1888 performance of the comic show he had running in New York: Prinz Methusalem, a loose English vaudeville adaptation of the 1877 light operetta by the Viennese waltz-composer Johann Strauss II. Members of the hometown New York Giants and the visiting Chicago White Stockings baseball teams had announced they would be attending the show, and Hopper wanted to tease them with something about baseball.

A New York Sun writer in the audience transcribed the poem (slightly inaccurately), and the paper immediately ran it, giving the poem its first national publication. A.M. Juster suggests a different chronology, with the Sun the source of De Wolf Hopper’s awareness of the verses. Regardless, Hopper would go on to perform the poem thousands of times (amazingly, the Baseball Almanac has the audio of one of his readings), and over the next few years the authorship and original of Thayer’s poem become widely known. And something more than widely known.

An awkward man, less successful than his classmates, Thayer is remembered for little else, and the poem has gone on to become the most-recited and most-reprinted of baseball poems. It’s in a trotting heptameter, a seven-foot form that has some serious uses (think of Byron’s “There’s not a joy the world can give like that it takes away”) but would eventually come to seem primarily a comic meter in English. Something about the rush of Thayer’s couplets, arranged in quatrains, caught the public’s ear at the time — and still does. A poem for tomorrow’s Opening Day of the 2024 baseball season.

Casey at the Bat

by Ernest Thayer

The Outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville nine that day: The score stood four to two, with but one inning more to play. And then when Cooney died at first, and Barrows did the same, A sickly silence fell upon the patrons of the game. A straggling few got up to go in deep despair. The rest Clung to that hope which springs eternal in the human breast; They thought, if only Casey could get but a whack at that — We’d put up even money, now, with Casey at the bat. But Flynn preceded Casey, as did also Jimmy Blake, And the former was a lulu and the latter was a cake; So upon that stricken multitude grim melancholy sat, For there seemed but little chance of Casey’s getting to the bat. But Flynn let drive a single, to the wonderment of all, And Blake, the much despis-ed, tore the cover off the ball; And when the dust had lifted, and the men saw what had occurred, There was Johnnie safe at second and Flynn a-hugging third. Then from 5,000 throats and more there rose a lusty yell; It rumbled through the valley, it rattled in the dell; It knocked upon the mountain and recoiled upon the flat, For Casey, mighty Casey, was advancing to the bat. There was ease in Casey’s manner as he stepped into his place; There was pride in Casey’s bearing and a smile on Casey’s face. And when, responding to the cheers, he lightly doffed his hat, No stranger in the crowd could doubt ’twas Casey at the bat. Ten thousand eyes were on him as he rubbed his hands with dirt; Five thousand tongues applauded when he wiped them on his shirt. Then while the writhing pitcher ground the ball into his hip, Defiance gleamed in Casey’s eye, a sneer curled Casey’s lip. And now the leather-covered sphere came hurtling through the air, And Casey stood a-watching it in haughty grandeur there. Close by the sturdy batsman the ball unheeded sped — “That ain’t my style,” said Casey. “Strike one,” the umpire said. From the benches, black with people, there went up a muffled roar, Like the beating of the storm-waves on a stern and distant shore. “Kill him! Kill the umpire!” shouted someone on the stand; And its likely they’d a-killed him had not Casey raised his hand. With a smile of Christian charity great Casey’s visage shone; He stilled the rising tumult; he bade the game go on; He signaled to the pitcher, and once more the spheroid flew; But Casey still ignored it, and the umpire said, “Strike two.” “Fraud!” cried the maddened thousands, and echo answered fraud; But one scornful look from Casey and the audience was awed. They saw his face grow stern and cold, they saw his muscles strain, And they knew that Casey wouldn’t let that ball go by again. The sneer is gone from Casey’s lip, his teeth are clenched in hate; He pounds with cruel violence his bat upon the plate. And now the pitcher holds the ball, and now he lets it go, And now the air is shattered by the force of Casey’s blow. Oh, somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright; The band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light, And somewhere men are laughing, and somewhere children shout; But there is no joy in Mudville — mighty Casey has struck out.

It may not be Byron, Milton, or Shelley, but some favorites win out none the less.

This poem is actually pretty brilliant and could outlast many that are more highly regarded, if baseball remains widely intelligible. No dissociation of sensibility here--it recognizes the comedy of taking the game so seriously, but fully participates in the emotions involved. If the reader doesn't actually feel the hope and disappointment, it's not the poem's fault.