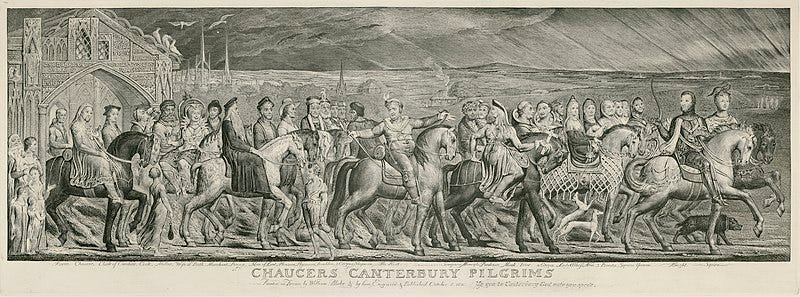

Today’s Poem: Canterbury Tales

The opening of Chaucer’s General Prologue and the joys of an English April

We begin the end of April (famous in some quarters as the cruellest month) with that other immortal first line: the opening of the General Prologue of The Canterbury Tales. With a dependent clause, “Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote,” Geoffrey Chaucer (d. 1400) sweeps us up into that April with its rains and its sunshine, its birds and tender growing things. He catapults us into a world vivid with life, even though it comes to to us from the fourteenth century, in a language that is almost, but not quite, our own.

Chaucer’s Middle English is the bridge between Old English, the language imported into Britain by invading Germanic tribes in the fifth century, and the early-modern English of the Tudor era and Shakespeare. His English is the language of an England in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest. It represents the closing of the gap between French, the language of courtier and diplomat, and the various Old En…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poems Ancient and Modern to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.