Today’s Poem: Barbara Frietchie

Shoot, if you must, this old gray head, / But spare your country’s flag

Barbara Frietchie

by John Greenleaf Whittier

Up from the meadows rich with corn, Clear in the cool September morn, The clustered spires of Frederick stand Green-walled by the hills of Maryland. Round about them orchards sweep, Apple- and peach-tree fruited deep, Fair as a garden of the Lord To the eyes of the famished rebel horde, On that pleasant morn of the early fall When Lee marched over the mountain wall, — Over the mountains winding down, Horse and foot, into Frederick town. Forty flags with their silver stars, Forty flags with their crimson bars, Flapped in the morning wind: the sun Of noon looked down, and saw not one. Up rose old Barbara Frietchie then, Bowed with her fourscore years and ten; Bravest of all in Frederick town, She took up the flag the men hauled down; In her attic window the staff she set, To show that one heart was loyal yet. Up the street came the rebel tread, Stonewall Jackson riding ahead. Under his slouched hat left and right He glanced: the old flag met his sight. “Halt!” — the dust-brown ranks stood fast. “Fire!” — out blazed the rifle-blast. It shivered the window, pane and sash; It rent the banner with seam and gash. Quick, as it fell, from the broken staff Dame Barbara snatched the silken scarf; She leaned far out on the window-sill, And shook it forth with a royal will. “Shoot, if you must, this old gray head, But spare your country’s flag,” she said. A shade of sadness, a blush of shame, Over the face of the leader came; The nobler nature within him stirred To life at that woman’s deed and word: “Who touches a hair of yon gray head Dies like a dog! March on!” he said. All day long through Frederick street Sounded the tread of marching feet: All day long that free flag tost Over the heads of the rebel host. Ever its torn folds rose and fell On the loyal winds that loved it well; And through the hill-gaps sunset light Shone over it with a warm good-night. Barbara Frietchie’s work is o’er, And the Rebel rides on his raids no more. Honor to her! and let a tear Fall, for her sake, on Stonewall’s bier. Over Barbara Frietchie’s grave Flag of Freedom and Union, wave! Peace and order and beauty draw Round thy symbol of light and law; And ever the stars above look down On thy stars below in Frederick town! ═══════════════════════

There are poems that are damaged by our knowing too much about them. Often, of course, that’s a sign that they were over-hyped or over-wrought, over-spread across the nation because they gave expression to a particular cultural mood at a particular historical moment.

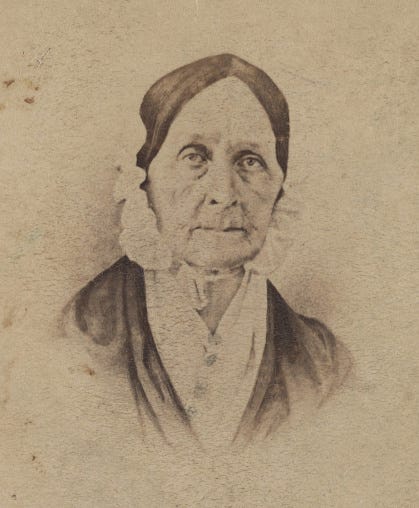

“Barbara Frietchie” by John Greenleaf Whitter (1807–1892) is one such. The poem was widely anthologized for a century after its 1863 publication, and why not? It tells the patriotic story of a ninety-year-old woman who bravely raises the Union flag over the heads of marching rebels in Frederick, Maryland — all in competent and memorizable tetrameter couplets, with a few nice lines: “Up from the meadows rich with corn,” for example, and, especially, “Who touches a hair of yon gray head / Dies like a dog! March on!” Here at Poems Ancient and Modern we’ve already offered Whittier’s “Telling the Bees” and “Snow-Bound,” and “Barbara Frietchie” would join “Snow-Bound” as a standard in American textbooks and anthologies.

But something about the poem’s success seemed to invite the imp of perversity to settle in critics, who gathered contemporary accounts to determine that the incident probably didn’t happen, and if it did, the woman involved was not Barbara Frietchie, although she was a genuine resident of Frederick.

The setting is the 1862 invasion of Maryland by the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, led by Robert E. Lee, with Stonewall Jackson one of his key lieutenants. The invasion was turned back at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862 — the bloodiest day in the Civil War (or any other time in American history) with over 22,000 casualties. Lee won the battle, in the sense of losing fewer soldiers, but he was unable to dislodge the Northern forces and his retreat afterward made the battle effectively a Union victory.

Along the way, Stonewall Jackson did march through the town of Frederick, and Whittier would later write:

This poem was written in strict conformity to the account of the incident as I had it from respectable and trustworthy sources. It has since been the subject of a good deal of conflicting testimony, and the story was probably incorrect in some of its details. It is admitted by all that Barbara Frietchie was no myth, but a worthy and highly esteemed gentlewoman, intensely loyal and a hater of the Slavery Rebellion, holding her Union flag sacred and keeping it with her Bible; that when the Confederates halted before her house, and entered her dooryard, she denounced them in vigorous language, shook her cane in their faces, and drove them out; and when General Burnside’s troops followed close upon Jackson’s, she waved her flag and cheered them. It is stated that May Quantrell, a brave and loyal lady in another part of the city, did wave her flag in sight of the Confederates. It is possible that there has been a blending of the two incidents.

It’s interesting to note Whittier’s treatment of Stonewall Jackson — who, in truth, rounded up free black men in Frederick, chaining them as slaves and taking them with his troops. Whittier was certainly no friend of the South: An ardent supporter of Lincoln and the Union, he was devoted to abolitionism. But in Whittier’s picture of Jackson, one can begin to see the path that reconciliation would take after the war, settling — notably with the Centennial of 1876 (after the problems with Reconstruction) — on a popular myth that the Southern leaders, especially Lee and Jackson, were noble characters fighting for an ignoble cause. They were to be viewed in sorrowful admiration.

This was a rotten solution to the race problem that has plagued America since the beginning, as it contributed to decades of a national acceptance of — a national shrug about — Jim Crow laws and segregation in the South. But the nation’s exhaustion at the time was real, and even in 1863, Whittier was in tune enough with the national mood to express the North’s desire both to win and to resolve the war: “With malice toward none, with charity for all.”

Whittier knew what he was about. This is Parlor Poetry at its best. As usual, the commentary here is spot on. Exhaustion...yes. It leads to apathy and the acceptance of a new abnormal norm. So, one tries to think of Jackson and Lee as men other than what they were--traitors on the wrong side of history. But who is winning now? Aren't the toppled statues of Lee and Jackson rising again?

I am not American, and so I take this poetic rendering of a wartime incident with more universal sympathy. While the arts are frequently used as propaganda, good art speaks beyond its historical particularities. To me this poem is about the lady of the title. The ideals that she embodies shine out over and above the actual conflict of the American Civil War, a fact demonstrated here by the words of Stonewall Jackson. The courage, patriotism, and mettle of Barbara Frietchie are traits that all Americans admire, both sides of the Mason-Dixie Line. To identify--and perhaps write a poem about--those things that can be agreed upon by disparate parties is excellent ground upon which to build unity in the midst of disunity.