Aero-Laughter

by Robert McAlmon

You’ve never laughed Until the world Has been beneath you A mosaic map of lines and dots, Called roads and mountains By minute moving spots Named men. The jollity Of this petty panorama! When your plane, Overcome with mirth, Ripples in air pockets With uncontrollable lurches, Nosing down with a dart To frighten the tiny earth; Then recovers, fleeting To heights beyond eyes’ seeing, Far from ears’ hearing, You are all tense With the comedy of life And the world’s being. At night the stars Chortle gleefully with you. The moon beams, Benignly sharing your joy. Thinking: “I laugh! The world?—rather one world, The buffoon of them all.” ═════════════════════════

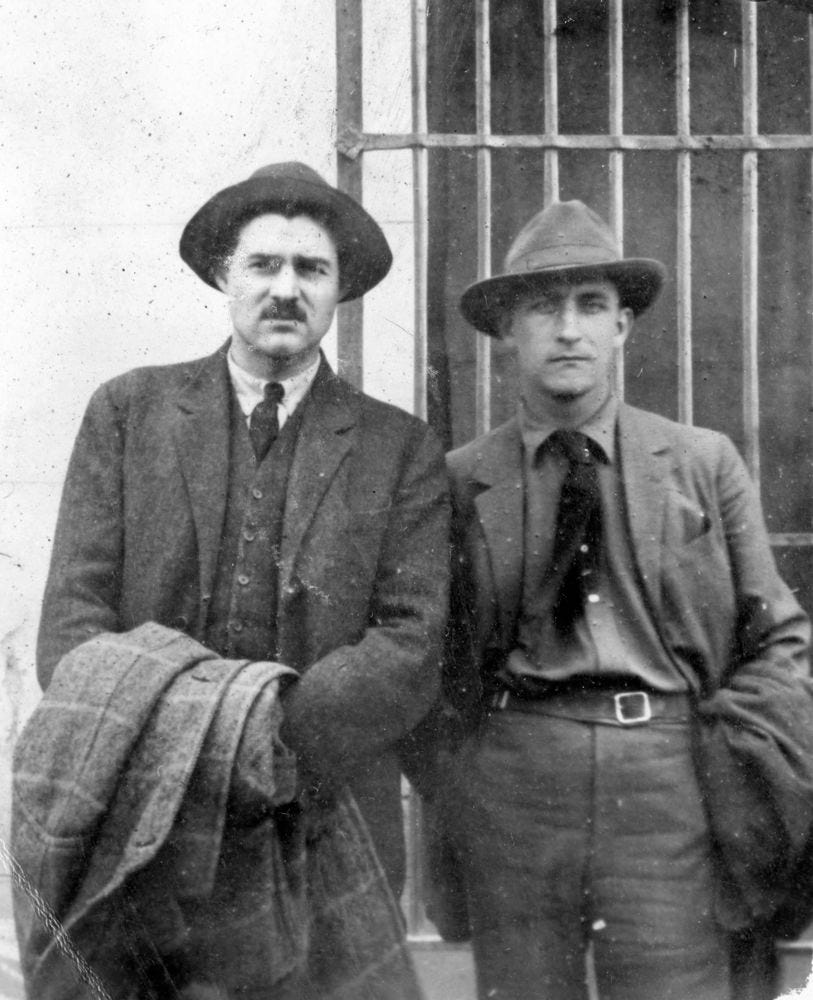

Robert McAlmon (1895–1956) is a fine example of a randfigur, literally “a side character” but a useful word when talking about the people who seem to pop up repeatedly in the biographies of more-prominent figures. Among English-speakers in Paris after the First World War, among those who sat down to eat at the Moveable Feast, McAlmon almost invariably makes an appearance in their memoirs.

Thus, for example, he typed up the handwritten manuscript of Ulysses for James Joyce. A male model, he married a wealthy Englishwoman, acting as cover for her affair with Hilda Doolittle, and used his wife’s money to start Contact, a publishing house in Paris, where he brought out Ernest Hemingway’s first book — along with William Carlos Williams’s Spring and All.

Ford Madox Ford, Mina Loy, Gertrude Stein, Djuna Barnes, Ezra Pound: If they were avant-garde, McAlmon knew them, partied with them, had affairs with them, and often published them.

Curiously, his own best-known writings were short stories and memoirs about his childhood in the American Midwest, especially the 1924 Village: As It Happened Through a Fifteen Year Period. Though accounts of him often speak of an itinerant life as a child, the South Dakota historian Jon Lauck and English professor Justin Blessinger recently pointed out to me that most of the places in which he was young were actually in a small circle around the town of Madison, South Dakota, where his father was a Presbyterian preacher, filling in for clergy in the area.

That’s worth mentioning, for one of his childhood friends was Eugene Vidal (1895–1969), father of the writer Gore Vidal (and so, of course, randfigur McAlmon makes an appearance in Gore Vidal’s 1996 memoir, Palimpsest). With McAlmon only a month older than Eugene Vidal, the two knew each other in Madison, and Vidal, a well-known athlete, would go on to become a major figure in the burgeoning aviation industry after the war, eventually serving as President Roosevelt’s chief aviation advisor in the 1930s.

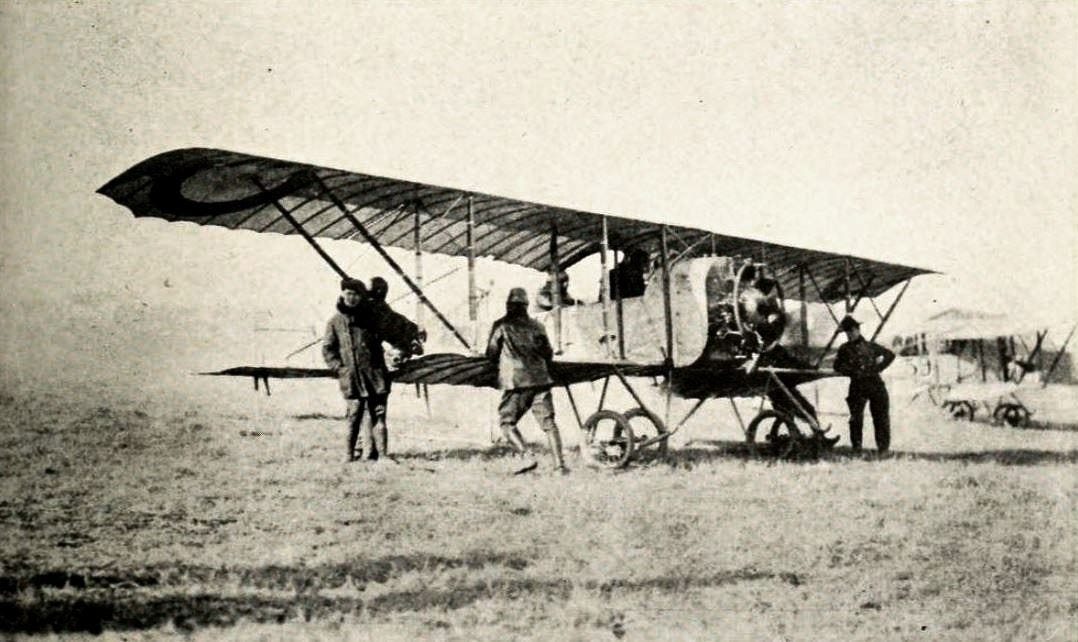

McAlmon, too, was an airman, enlisting in the United States Army Air Corps in 1918 to fight the war. It was as a flight veteran that he published a 1919 set of poems in Poetry magazine — the first of which, “Aero-Laughter,” we offer as Today’s Poem.

The history of airplane literature is not well documented (an under-developed topic for any interested scholar), but one would probably have to begin with William Butler Yeats’s 1918 poem, “An Irish Airman Foresees His Death,” although Carl Sandburg’s “To Beachy, 1912,” in his 1916 collection Chicago Poems, predates it.

Add in some of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s 1930s lyrical prose descriptions of flight — Southern Mail, Night Flight, or Wind, Sand and Stars — and Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s 1944 novella, The Steep Ascent. The poetry of the Second World War includes the air-force poems of Richard Eberhart’s “The Fury of Aerial Bombardment,” William Everson’s “The Raid,” Randall Jarrell’s over-anthologized “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” and John Gillespie Magee’s popular sonnet “High Flight.”

Robert McAlmon’s “Aero-Laughter” comes early in this mix, a free-verse account of flying a plane that finds manic joy in the disconnection from ordinary things: roads and mountains turned to a “mosaic map of lines and dots,” and men to “minute moving spots.”

In the opening stanza, the laughter is the pilot’s: “You’ve never laughed / Until the world / Has been beneath you.” But in the second stanza, the laughter extends to the plane: “When your plane, / Overcome with mirth, / Ripples in air pockets / With uncontrollable lurches.”

And in the third stanza, the cosmos itself joins the manic laughter. “At night the stars / Chortle gleefully with you,” McAlmon writes — joined soon by the moon’s “Benignly sharing your joy.” And the earth? It is “The buffoon of them all.”

Excellent piece! Let’s not forget High Flight (John Gillespie Magee) - a bit hackneyed, but still good stuff! Second World War, though; I haven’t come across any other aviation war poetry from WW1, apart from the Irish Airman.

Thanks for introducing me to this poem. The conjunction of transcendence and giddiness is novel for me.