Shine, Perishing Republic

by Robinson Jeffers

While this America settles in the mould of its vulgarity, heavily thickening to empire, And protest, only a bubble in the molten mass, pops and sighs out, and the mass hardens, I sadly smiling remember that the flower fades to make fruit, the fruit rots to make earth. Out of the mother; and through the spring exultances, ripeness and decadence; and home to the mother. You making haste haste on decay: not blameworthy; life is good, be it stubbornly long or suddenly A mortal splendor: meteors are not needed less than mountains: shine, perishing republic. But for my children, I would have them keep their distance from the thickening center; corruption Never has been compulsory, when the cities lie at the monster's feet there are left the mountains. And boys, be in nothing so moderate as in love of man, a clever servant, insufferable master. There is the trap that catches noblest spirits, that caught — they say — God, when he walked on earth.

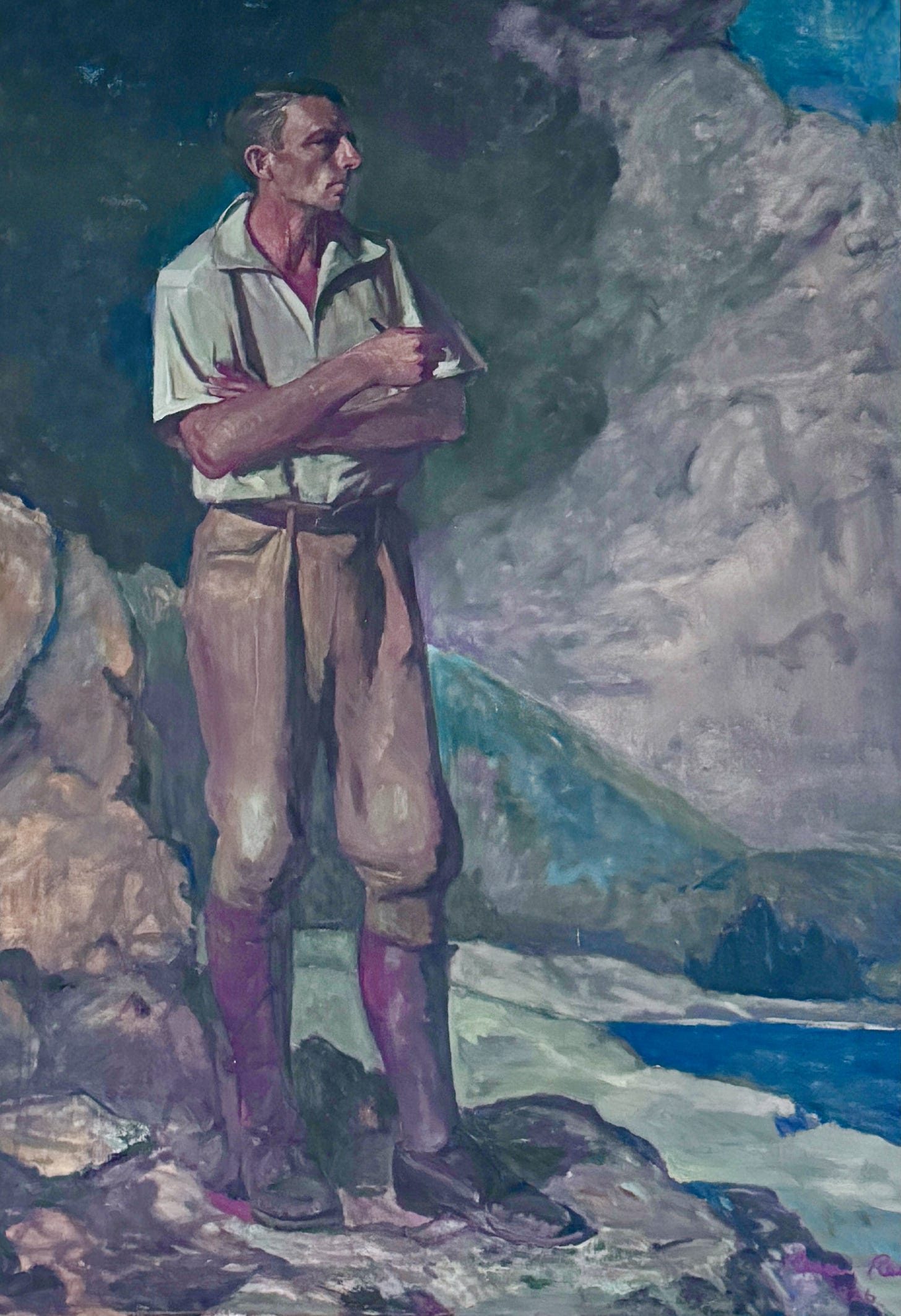

What’s remarkable about about “Shine, Perishing Republic,” what has always struck me about the poem, is the dogged honesty that Robinson Jeffers (1887–1962) brings to his thought.

As it happens, Jeffer’s thought is not particularly original — or particularly good. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s short story “May Day,” in his 1922 Tales of the Jazz Age, is, I think, a more profoundly realized claim of American decline and the material vileness of culture after World War I.

Still, Jeffers’s early 1920s poem gives us his picture of America settling “in the mould of its vulgarity, heavily thickening to empire,” while “protest, only a bubble in the molten mass, pops and sighs out, and the mass hardens.” And Jeffers offers a frame in which to put that picture, a way for us to live with it — essentially a Stoic abstraction, a rising up in mental fortitude to recognize that all that lives must die. All that flourishes also fades; nations as well as fruit trees are part of the cycles of time: “not blameworthy; life is good, be it stubbornly long or suddenly / A mortal splendor: meteors are not needed less than mountains: shine, perishing republic.”

The notion that America was coming to an end in the early 1920s was simply wrong, an anxious presentism that overwhelmed sensible prognosis. But what has always struck me about the poem is the honesty with which Jeffers pursues his thought, however mistaken — the honesty makes the poem more noteworthy than his weak 1930s follow-ups, “Shine, Republic” and “Shine, Empire,” or even his often-quoted “Be Angry at the Sun” (another recommendation of Stoic abstraction in the face of a corrupt political order).

Written in five unrhymed free-verse couplets (with the long lines, nine or ten stresses each, that became Jeffers’s trademark), “Shine, Perishing Republic” makes a turn in the fourth couplet. The easy path — the road of the self-congratulatory, the stupid, and the dishonest — would be to wrap things up after the the first three couplets: (1) America is dying in its corruption. (2) But, then, dying is natural. (3) And at least we can take some consolation in the brief splendor of the republic.

Jeffers, however, sees the price of such Stoic abstraction, a price that comes when we ask ourselves what happens to the next generation. “But for my children,” he begins the fourth couplet, a phrase in the poem that has always moved me. And what is the answer for his children after the vision of a dying nation alleviated only by a Stoic sense of universal decay? “I would have them keep their distance,” he declares, for “when the cities lie at the monster’s feet there are left the mountains.” Flee to the hills, in other words. Let the social order break up into small communities of the saved.

Perhaps a poet less hard-headed, less committed to honesty, would have let it end there. But Jeffers sees — and decides to accept — the consequence of telling his children to flee. He understands and is willing to pay the cost of abandoning the cities. “And boys,” the fifth couplet begins, addressing his children, “be in nothing so moderate as in love of man,” for “There is the trap that catches noblest spirits, that caught — they say — God, when he walked on earth.” The price of Stoic abstraction and social abandonment is ceasing to care for mankind. The cost is the loss of Christian love.

I like the poem but I really love the title.

I keep my Collected Poems of Czeslaw Milosz on the shelf right next to my collected Robinson Jeffers for a reason. "No one with impunity / Gives to himself the eyes of a god. So brave, in a void, / You offered sacrifices to demons...Better...to implore protection / Against the mute and treacherous might / Than to proclaim, as you did, an inhuman thing." ("To Robinson Jeffers," 1963)